Interlopers on Social Media: Feminism, Women of Color and Oppression

Interlopers on Social Media: Feminism, Women of Color and Oppression

By @Prisonculture and Andrea Smith

Before writing this piece, we thought about whether we should bother. Was this a discussion worth engaging? Ultimately, we decided that we had some thoughts to share and that it was worth it to add our voices to the ongoing discussion about the nature of online dialogue within feminism. As women of color who identify as feminist and who engage online, we are implicated in this conversation. We hope that the following words, written quickly, will resonate with some. Feel free to share your thoughts in the comments section.

Once upon a time, not long ago, there existed a place online where everything was civil and nice. In that place, people were able to engage in enlightened and evolved dialogue and they felt happy and safe. All of this changed when unruly and fearful invaders entered that place in significant numbers. The civil and nice space in Cyberland called “Twitter” became mean and unproductive. Soon the ‘pioneers’ of Cyberland vociferously expressed their disapproval and most importantly their fears of the invaders. They used their loud speakers to broadcast their displeasure and to castigate the new arrivals for making Twitter toxic.

This is obviously an oversimplified description of what’s currently being called the “Feminist Twitter Wars.” However, what’s been happening online on various platforms is really a raucous and contentious discussion about who owns feminism. The traditional story that’s told in the U.S. is that there have been 3 (sometimes 4) historical “waves” of feminism. Usually, women of color appear in significant numbers in the third wave seemingly out of nowhere to join the struggle. When they join however, they bring disruptions through their demands for inclusion and their insistence about addressing previously overlooked issues. These disruptions are portrayed almost always as particularly jarring to the white women ‘founders’ of U.S. feminism. This incomplete and selective telling of a feminist history has been contested by many women of color over the years. Yet the idea that women of color (particularly black women) are interlopers and disruptive presences within the feminist movement has persisted.

In an ideal world, women of color’s critiques of a feminist future would be welcomed as gifts. Because the truth is that in order to build a mass movement that will uproot oppression, we are going to need everyone. Because we know that organizing means failing more often than not, new voices and ideas would be embraced as helping to end global oppression. After all, how much better is it to have a platform for sharing and discussing ideas that can encompass thousands rather than just a dozen of your friends? This should be seen as a boon and yet it is not. We need to ask why…

Over the past 10 to 15 years in particular, feminist spaces have been concerned with and consumed by an Ahab like quest for building and enforcing “safe space.” As women of color, who live under white supremacy, settler colonialism, heteronormativity, capitalism and more, we know that such a place doesn’t actually exist. More importantly, what we have seen over the years is that “safe spaces” usually mean excluding us. They sometimes mean using “safety” as a substitute for “never uncomfortable spaces.” In this conceptualization, safety is often used as a cudgel to silence and to further marginalize.

Christina Hanhardt’s important new book Safe Space, addresses some of these concerns:

“I, too, am not convinced that safety or safe space in their most popular usages can or even should exist. Safety is commonly imaged as a condition of no challenge or stakes, a state of being that might be best described as protectionist (or, perhaps, isolationist)…The quest for safety that is collective rather than individualized requires an analysis of who or what constitutes a threat and why, and a recognition that those forces maintain their might by being in flux. And among the most transformative visions are those driven less by a fixed goal of safety than by… freedom.” (p. 30)

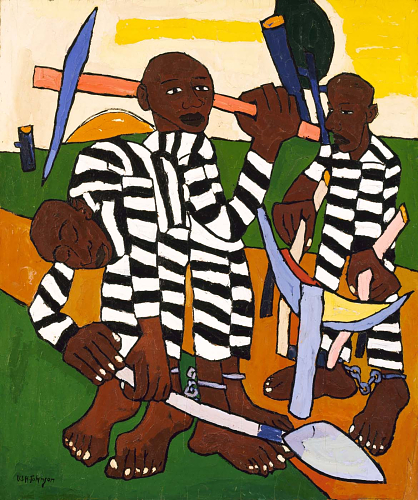

![Scottsboro Mothers [photoprints from 1934 negative], photographer: Scurlock, Addison N. 1883-1964](https://www.usprisonculture.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/01/scottsboromothers.jpg)