Yesterday was a good day.

Cece McDonald was released from prison after being unjustly incarcerated for 19 months. Adding insult to injury, she was locked up in a men’s prison despite being a woman. Many people rejoiced including Cece herself who was obviously thrilled to be out of prison.

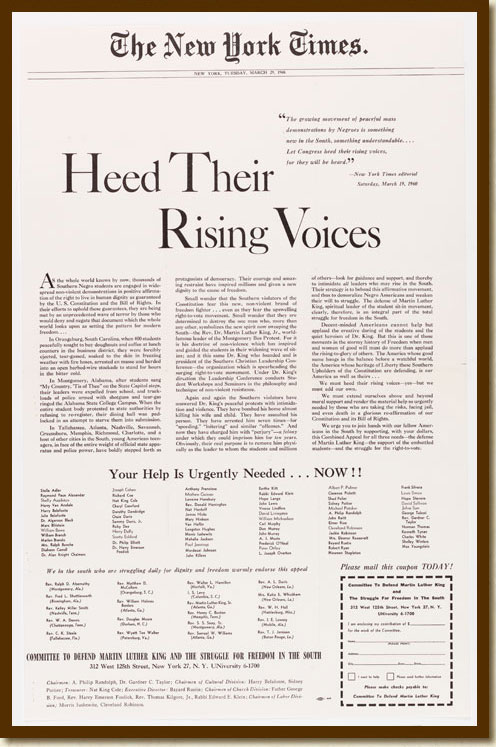

Cece with Laverne Cox leaving prison

I noticed a number of people on social media remarking that Cece was “free.” I thought of my friend Marcus who several years ago reprimanded me for applying this term to him. We were eating lunch about a month after he was released from serving five years in prison. I said, “So, how does it feel to be free?” He looked at me in his soul-searching way and replied: “I wasn’t free when I went in and I sure as shit ain’t free now.” I felt as though I had been punched in the gut because I of course knew this to be true. Since that conversation, I have tried to avoid using the term “free” when I talk about formerly incarcerated people.

Cece will suffer the collateral consequences of a criminal conviction and incarceration for years to come. This is what I call the ‘invisible shackles of the carceral state.’ Across the country, almost 6 million people are ineligible to vote in elections as a result of a criminal conviction. Cece who lives in Minnesota will be barred from voting until her “felony conviction record [is] discharged, expired, or completed.” This means that she will be disenfranchised for several years. She is one of the “lucky” ones who won’t be permanently barred from participating in a critical aspect of civic life.

Thankfully Cece has a supportive community of friends around her and has already found a place to live. However, most returning citizens find themselves scrambling to afford and rent apartments upon their release from prison. In many states, formerly incarcerated people are banned from public housing. Some find a place in halfway houses. Many more are made homeless.

In 2014, a criminal record is almost synonymous with permanent under and unemployment. In the current depressed economy, there are at least three applicants (usually more) for each open position. Employers have their pick of people to hire. Returning citizens are low on their list. Without a path to legal employment, many formerly incarcerated people turn to the informal economy to survive. This often leads them back to prison (PDF) within three years of their release.

In his searing memoir 7 Long Times, Piri Thomas writes poignantly about the psychological impact of his incarceration and his struggle to re-acclimate upon being released:

It took me a long time before I was able to get the prison cockroaches out of my head. I’d wake up at home from nightmares that I was back in prison hearing the horrors, the curses and screams, reliving the tensions, anger, and pain, my body drenched in cold sweat. It would take minutes for me to realize I was at home.

When I first came home, I couldn’t break the habit of waking up in the morning half-asleep, getting into my clothes and stumbling around my bedroom looking for the toilet bowl and wash bowl, then standing like a damn fool in front of my bedroom door waiting for the guard to spring the lock. While in prison, I had always fought against being institutionalized, but some of its habits had rubbed off on me a little too damn deep. Even now, twenty-four years later, I still have an occasional nightmare that I’m back in prison.

It’s not easy to “leave prison behind.” Many formerly incarcerated people battle depression and other mental health issues upon their release. Often without access to health insurance, many do not get counseling or any other support for their psychological struggles.

As a black transgender woman, Cece is at risk of violence every time she leaves the house as evidenced by the attack that led to her unjust imprisonment. In 2013, the National Coalition of Anti-Violence Programs documented at least 14 homicides of transgender women. The numbers are almost certainly much higher. The heightened risk of violence is another kind of cage, curtailing one’s movements and impinging on any sense of safety.

So while we rightly celebrate the fact that Cece has been released from prison and wish her well, let’s not forget the injustice that she was ever incarcerated in the first place. Let’s also remember that she is still dogged by the ‘invisible shackles of the carceral state’ so it behooves us to reframe the idea of ‘freedom.’ Finally, let’s make sure to commit ourselves to fighting for the release of the thousands of other trans people who are currently still locked up in our prison nation. In a letter from prison, Cece wrote:

“The real issues are the ones that affect all prisoners. People should get involved in changing policies that keep people in prisons, like exclusion from employment, housing, public assistance…These are just a few things that will keep people out of prisons and lead to the dismantling of these facilities.” (cited by Vikki Law)

Cece gets it. I hope others will too.