I am thrilled to report that the project I’ve been working on for the past few weeks was handed over to a friend to design. I’ve gotten a sneak peak of the publication and it’s beautiful. On short notice, many people came together and came through. With only a few snags along the way, it was a joy to work on this project. If you’ve read this blog even just once, you’ll recognize how much history matters to me. I very much wanted to put Marissa Alexander’s case in historical context in an accessible way. I think that we achieved this goal. I am so grateful to everyone who contributed to the project and am looking forward to unveiling the finished product(s) soon.

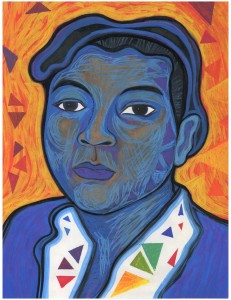

As a preview, I am sharing Rosa Lee Ingram’s story along with art created especially for this project by my friend Billy Dee. The project includes eleven other stories of women of color (including Marissa) who were criminalized for self-defense. Along with the publication which we will use to raise funds for Marissa’s legal defense, we are also planning an exhibition here in Chicago in July. I look forward to sharing more soon.

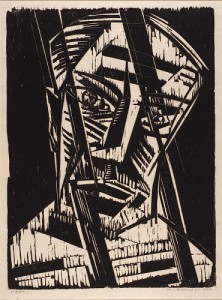

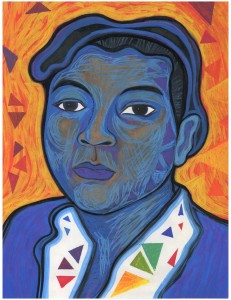

Rosa Lee Ingram by Billy Dee (2014)

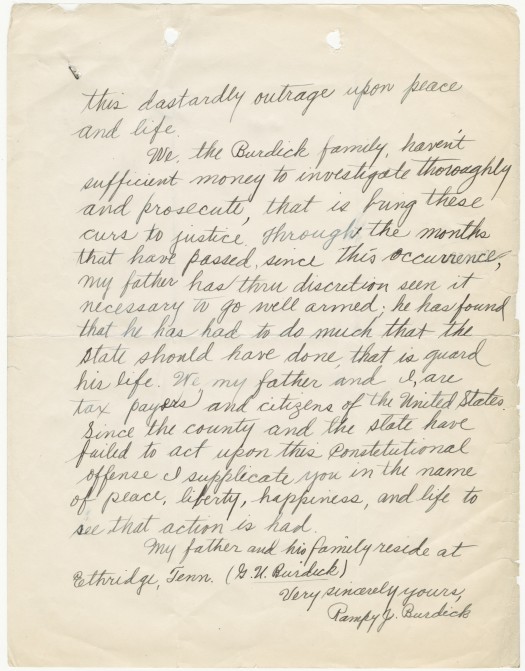

In 1954, 90 year old

Mary Church Terrell, a lifelong activist, declared: “I’m going back to Georgia.” Terrell, chairwoman of the Women’s Committee for Equal Justice, was announcing a “Mother’s Day crusade” that she and other women would lead to once again advocate for the release of Rosa Lee Ingram and her two sons. By this time, all three had already spent the better part of six years in prison.

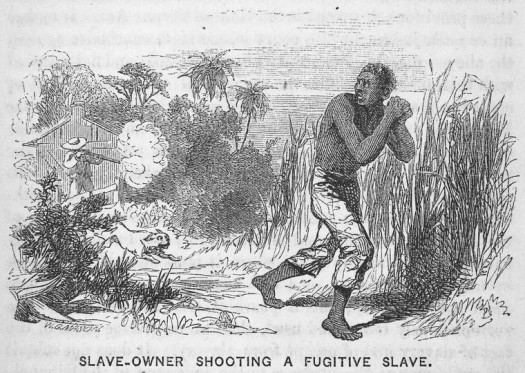

In 1948, Rosa Lee Ingram, a widowed mother of 12 children, was convicted and sentenced to death along with her two sons, Wallace & Sammie Lee, for killing a white man in self-defense. Ingram, a sharecropper, lived on the same property as 64 year old John Stratford, also a sharecropper. She had endured years of harassment by him.

On November 4 1947, an argument that allegedly began because Stratford was angry that some hogs had crossed into his property quickly escalated when he tried to force Rosa Lee into a shed to have sex with him. She fought back. Ingram’s 16 year old son Wallace heard the commotion and ran to help his mother. He warned Stratford to “stop beating mama” and when he did not, Wallace picked up a gun and slammed it on his head. He and his mother left Stratford lying on the ground unaware that he was dead.

After Rosa Lee, Wallace, and another son named Sammie Lee were convicted of first degree murder on January 26 1948 in a one day trial, they were sentenced to die in the electric chair on February 27. There was immediate outrage at the conviction and death sentence. Family members of the Ingrams, including Rosa Lee’s mother Mrs. Amy Hunt, asked religious and other organizations for funds to support an appeal. The NAACP and the Georgia Defense Committee pledged their support and contributed money.

Supporters across the country organized protests. The widespread public pressure worked: in March 1948, Judge W.M Harper set aside the death penalty and commuted the family’s sentences to life in prison. Wallace was 16 years old and his brother Sammie Lee was only 14.

While the NAACP actively raised money and provided legal support during the case, Black women actually drove the campaign to free Rosa Lee Ingram and her sons from prison. In 1949, a group of Black women formed the National Committee for the Defense of the Ingram Family. In addition to Mary Church Terrell who served as its national chair, the group included luminaries like Maude White Katz, Eslanda Robeson, Shirley Graham Du Bois, and Charlotta Bass.

The committee organized an action in spring 1949, sending 10,000 Mother’s Day cards and a petition with 25,000 signatures to President Truman insisting that Mrs. Ingram be freed.

The Ingram Defense Committee also reached out for international support in its campaign. In September 1949, members asked W.E.B. DuBois to write a petition to the UN Commission on Human Rights asking that it debate her case.

For years afterwards, contingents of women continued to organize diligently insisting that the Ingrams be paroled and freed from prison. They organized “Mother’s Day crusades” which included visits to local politicians asking them to intervene in securing the release of the Ingrams. Georgia finally released Rosa Lee Ingram and her sons on August 26 1959 after 12 years of incarceration. This would not have happened if not for the consistent agitation and organizing on their behalf by thousands of people across the world, and particularly Black women. It was that organizing that saved their lives.