The Un-Mothering of Black Women…

Note: It’s Mother’s Day. For several years now, I’ve been considering the idea of un-mothering. I share my inchoate thoughts here today. They are part & parcel of my ongoing consideration of how blackness functions across categories, social locations, and histories. In other words, these are jumbled ideas and you probably shouldn’t bother to read them. I’m trying to work through some ideas and writing them down helps that process…

The title of this post was originally “Punishing Black Motherhood.” In the U.S., black mothers have been and continue to be punished and controlled in various ways. Dr. Dorothy Roberts writes brilliantly about this phenomenon in two books and several articles. For example, “Prison, Foster Care, and the Systemic Punishment of Black Mothers” in the UCLA Law Review provides a good analysis of how the criminal legal and child welfare systems work together to police and control black women’s bodies and families. She writes that the systems “function together to discipline and control poor and low-income black women by keeping them under intense state supervision and blaming them for the hardships their families face as a result of societal inequities (p. 1491).” She also points out that stereotypes about black women as ‘welfare queens’ and ‘matriarchs’ subject them to and reinforce punitive policies.

Anecdotal and empirical evidence support Dr. Roberts’s claims. Over the past few years, however, I’ve been considering the idea of “un-mothering” as it relates specifically to black American women. Connie Chung has used the term (un)mothering to discuss “the politics of representation in documenting the homeless female ‘other’.” The concept of un-mothering that I advance focuses on the ways that the state and society actively & violently threaten, remove, disappear, and kill black women’s children. Through this process, black women become un-mothers having (sometimes) given birth and then had their children disappeared. For those women whose children are still in their care, the threat of un-mothering looms. It’s unclear what impact this might have since the concept of un-mothering isn’t explicitly articulated within the culture.

At least a couple of times on this blog, I’ve quoted a passage in Solomon Northrup’s “12 Years A Slave” where he describes the closing scene of an 1841 New Orleans auction:

“…The bargain was agreed upon, and Randall [a Negro child] must go alone. Then Eliza [his mother] ran to him; embraced him passionately; kissed him again and again; told him to remember her — all the while her tears falling in the boy’s face like rain.

“Freeman [the dealer] damned her, calling her a blabbering, bawling wench, and ordered her to go to her place and behave herself, and be somebody. He would soon give her something to cry about, if she was not mighty careful, and that she might depend upon.

“The planter from Baton Rouge, with his new purchase, was ready to depart.

“‘Don’t cry, mama. I will be a good boy. Don’t cry,’ said Randall, looking back, as they passed out of the door.

“What has become of the lad, God knows. It was a mournful scene, indeed. I would have cried if I had dared.”

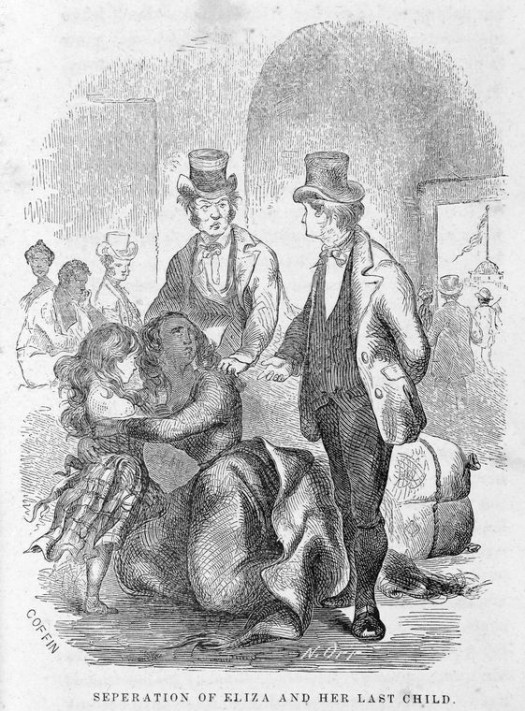

The 1853 edition of “12 Years A Slave” included the following illustration depicting the violent process of Eliza’s un-mothering.

I’m wondering if the demand that black women not be seen publicly grieving their dead and/or disappeared children can also be seen as an important dynamic in the process of un-mothering. White mothers are given license to show public emotion in a way that is not reciprocated for black women with children. Eliza cried as her child was ripped from her embrace. She was admonished by the slave master, Freeman, to stop bawling. A few weeks ago, I wrote about Trayvon Martin and Jordan Davis’s mothers: “In our historical moment, Sybrina and Lucia stand before the cameras stoic, pained, and tearless. One wonders if Freeman’s threat to Eliza not to cry has carried over somehow to 2014.” Murdering black women’s children un-mothers and denying them the right to be seen grieving seems key to the process.

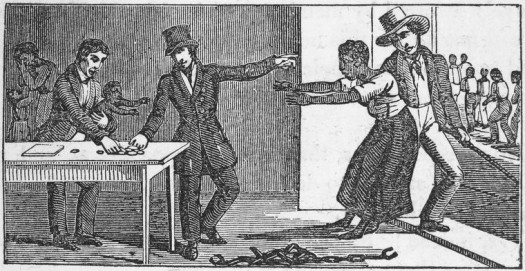

The following images of enslaved women being forcibly separated from their children also provide representations of un-mothering.

Mother being separated from her baby. (1862) Source: Slavery in South Carolina and the ex-slaves; or, The Port Royal Mission. By Austa Malinda

![[Woman pleading for the return of her two small children.] (1862) Source: Slavery in South Carolina and the ex-slaves; or, The Port Royal Mission. by Austa Malinda](https://www.usprisonculture.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2014/05/slavemother2-e1399616778238.jpg)

[Woman pleading for the return of her two small children.] (1862) Source: Slavery in South Carolina and the ex-slaves; or, The Port Royal Mission. by Austa Malinda

I recently learned that “Louisiana was the only slave state that passed legislation mandating the auction of children born to enslaved women inmates (Derbes, 2013, p.278).” This process of un-mothering was enabled by an 1848 Louisiana law titled: “An Act Providing for the disposal of such slaves as are or may be born in the Penitentiary, the issue of convicts.” Brett Josef Derbes (2013) documents that:

“Eleven children were torn away from their mothers in the Louisiana state prison at approximately the age of ten years old and sold into slavery, with the proceeds going to the ‘free school fund.’ Four of those children were sent to plantations owned by the lessees of the penitentiary. Records of the transactions were difficult to locate, and the children are documented in only a handful of official penitentiary records. The 1850 slave schedule revealed that the children were kept in the penitentiary as property of the state, but only the 1860 population census identified their place of birth as ‘born in the penitentiary’ (p.288).”

[To be continued…]