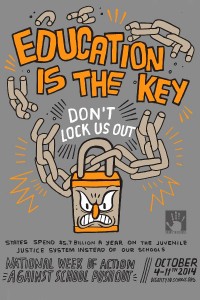

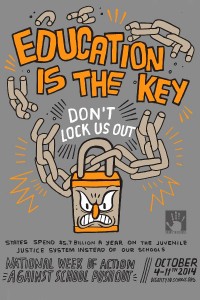

Tomorrow kicks of the 5th annual National Week of Action Against School Pushout. This year, my organization will join with youth, parents, teachers and community members in over 40 cities to resist school pushout and policing. Project NIA released a short paper this morning documenting the gains and challenges in the fight to end Chicago’s school to prison pipeline. I hope that those interested in these issues will read the paper authored by my friend, Dr. Michelle VanNatta.

Tomorrow kicks of the 5th annual National Week of Action Against School Pushout. This year, my organization will join with youth, parents, teachers and community members in over 40 cities to resist school pushout and policing. Project NIA released a short paper this morning documenting the gains and challenges in the fight to end Chicago’s school to prison pipeline. I hope that those interested in these issues will read the paper authored by my friend, Dr. Michelle VanNatta.

I thought that I would use the occasion of the week of action to offer an introduction to the school-to-prison pipeline for those who might be new to the concept. I’ll also provide some resources for those interested in further study.

Defining the School-to-Prison Pipeline (STPP)

In an article that we wrote earlier this year, Erica Meiners and I defined the STPP in this way:

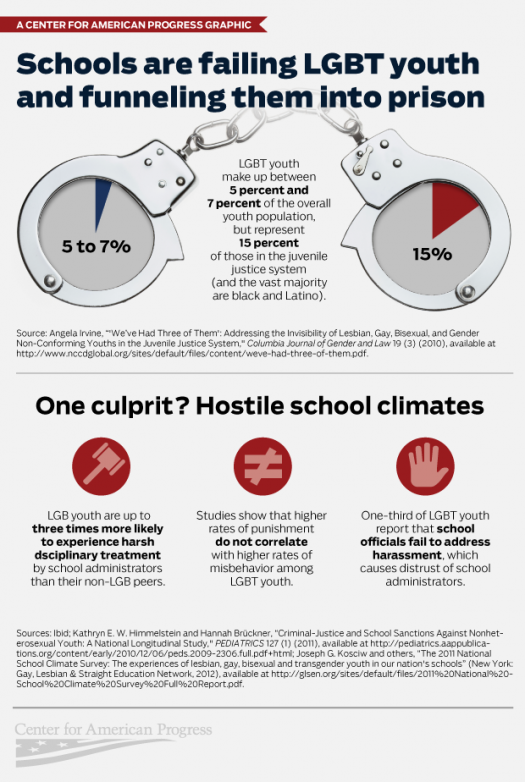

“Less a pipeline than a nexus or a swamp, the STPP is generally used to refer to interlocking sets of structural and individual relationships in which youth, primarily of color, are funneled from schools and neighborhoods into under- or unemployment and prisons.

While the US public education system has historically diverted non-white communities toward under-education, non-living wage work, participation in a permanent war economy, and/or incarceration, the development of the world’s largest prison nation over the last three decades has strengthened policy, practice, and ideological linkages between schools and prisons. Non-white, non-heterosexual, and/or non-gender conforming students are targeted for surveillance, suspended and expelled at higher rates, and are much more likely to be charged, convicted, and removed from their homes, or otherwise to receive longer sentences.”

Facts and Figures

To help provide some context for the scope and impact(s) of harsh school disciplinary policies, Project NIA created a short quiz to test your knowledge. Thanks to @cronehead and @MuffMacGuff who digitized this quiz. How do you fare?

Critique of the STPP Concept

Dr. Damien Sojoyner (2013) has challenged the concept of the school to prison pipeline. The abstract of his paper titled “Black Radicals Make for Bad Citizens: Undoing the Myth of the School to Prison Pipeline (PDF) summarizes his main argument:

“Over the past ten years, the analytic formation of the school to prison pipeline has come to dominate the lexicon and general common sense with respect to the relationship between schools and prisons in the United States. The concept and theorization that undergirds its meaning and function do not address the root causes that are central to complex dynamics between public education and prisons. This paper argues that in place of the articulation of the school to prison pipeline, what is needed is a nuanced and historicized understanding of the racialized politics pertaining to the centrality of education to Black liberation struggles. The result of such work indicates that the enclosure of public education foregrounds the expansion of the prison system and consequently, schools are not a training ground for prisons, but are the key site at which technologies of control that govern Black oppression are deemed normal and necessary.”

Others have offered other critiques of the STPP concept pointing out, for example, that we need think of the process of educational and societal marginalization as one that in fact begins from the cradle or even the womb.

Activism and Advocacy

The past decade has found increasing numbers of policy makers, advocates, academics, educators, parents, students, and organizers focusing explicitly on the relationships between education and imprisonment. A lot of organizing has happened around the issue of school pushout. The Dignity in Schools Campaign (organizers of the National Week of Action) brings together over 75 organizations across the country who are working to transform school discipline policies.

Just this week, advocates and organizers in California presided over Governor Jerry Brown’s signing of a bill to limit “school administrators’ use of an offense called “willful defiance” to suspend students in California schools.” This was the result of a long-term organizing campaign. Earlier, I referenced our newly released paper that documents some of the gains made by Chicago and Illinois organizers in the fight to interrupt the STPP.

Here are some organizations and projects advocating and organizing to end the STPP.

Teaching Youth About STPP: Curriculum Resources

We at Project NIA have developed several resources that can be used by educators and organizers to discuss the STPP with young people in particular. These resources have also been used by many people to lead discussions with adults as well. Others have also developed useful tools for teaching about the STPP.

Curriculum: Suspension Stories

Curriculum: NYCLU School-to-Prison Pipeline Workshop

Comic: School to Prison Pipeline by Rachel Marie-Crane Williams

One page comic with discussion questions: Sent Down the Drain

Find many other audio, video, etc… resources at Suspension Stories

Further Study

Disrupting the School-to-Prison Pipeline Edited by Bahena, Cooc, Currie-Rubin, Kuttner and Ng (2012)

From Education to Incarceration: Dismantling the School-to-Prison Pipeline Edited by Nocella, Parmar and Stovall (2014)

Punished: Policing the Lives of Black and Latino Boys by Victor Rios (2011)

There is a list of other reading here and here.

Over the course of this next week, I will be posting information about the specific components that make up the STPP. Stay tuned!