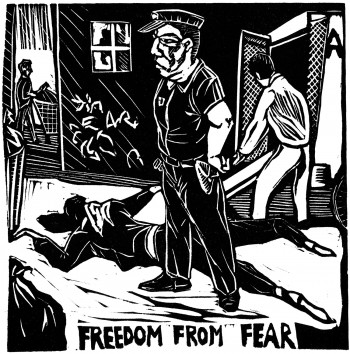

Officer Friendly Doesn’t Live Here: Policing Urban Youth

Last week, I blogged about the injustice of the practice of stop & frisk that so many people of color (especially young men of color) have historically endured.

Last week, I blogged about the injustice of the practice of stop & frisk that so many people of color (especially young men of color) have historically endured.

I would like to return to the topic of the relationship between the police and young people of color today. One of the most consistent themes that I hear from the young people who I work with is that they feel under siege by the police in their neighborhoods. They are consistently harassed and hassled for no reason other than their youth and skin color.

I have developed several workshops about police violence over the years and am currently working on a new one right now. In preparation for this, I have been reading a lot of research about how young people experience community policing.

I am particularly intrigued by a study of young African-American males that was conducted by Delores D. Jones-Brown. Dr. Brown surveyed 125 high school African American males regarding attitudes toward and contacts with the police. Her findings unsurprisingly suggest that a majority of the males report experiencing the police as a repressive rather than facilitative agent in their own lives and in the lives of their friends and relatives. The young respondents in her study complained of being stopped because they were suspected of dealing drugs or because they were out past curfew or because they were in the “wrong” neighborhood. Again, anecdotal evidence supports this as being true. One only needs to listen to Tupac Shakur in order to hear the exasperation and the barely contained rage at the treatment by police. Listen to Pat’s Justice and his Innocent Criminal Anthem to understand how deeply this experience of being harassed by the police cuts and harms.

In my experience, young people often express a sense of anger and feel as though they are being wronged. Unfortunately I have also heard some young people internalize this treatment and respond by claiming that people of color bring this scrutiny on to themselves by engaging in a disproportionate amount of criminal behavior. It always takes a lot of time to disabuse these youth of that idea. For some, self-hatred is deeply ingrained.

There is another thing still. Henry Giroux recently wrote about the concept of the punishing state and its growing power and impact over the lives of youth of color in his book Youth in a Suspect Society. The police have always been the enforcers of the punishing state. The militarization of schools with their security cameras, police patrols, and bathrooms on lockdown reinforces the idea that young people of color are threats to the state. Giroux also speaks to a “politics of disposability” for young people which serves to remove them from the realm of being deserving of support and resources. Over the past 20 years, young people of color have become increasingly the targets of policies and rules that suggest that they are in some ways already assumed to be “criminal.” Youth are being managed through the lens of crime, repression, and punishment. This has taken a great toll.

I have previously blogged about the silent mental health crisis that is decimating many young black men. In particular, I relied on the example of rapper DMX to make a larger point about the need to help young black men process their experiences with oppression. The daily harassment at the hands of the police is often experienced by young men of color as micro-aggressions that they have little power to resist without suffering potentially lethal consequences. This takes a toll on their physical and mental wellness. And yet too few educators, pastors, youth workers, parents address this issue with their sons and daughters. We must break the silence about this experience. It is crucial to healing our communities.

For old times sake, here is a classic by NWA:

Study Cited — Brown-Jones, Delores D. Debunking the Myth of Officer Friendly: How African American Males Experience Community Policing. Journal of Contemporary Criminal Justice 2000: 16; 209.