“A Black Woman’s Body Was Never Hers Alone…” A Rejoinder to Akin, Mourdock, & Gingrey

“A black woman’s body was never hers alone.”

This is a quote from Fannie Lou Hamer and I think that it speaks volumes. I am moved to write this morning because I have been feeling very triggered by the “discussion” about rape over the past couple of days. Once again, social media is abuzz with asinine comments made by another Republican Congressman about rape and pregnancy.

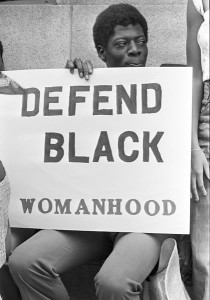

So I want to write about oppression and resistance today. More specifically, I’d like to focus on black women and girls’ resistance to sexual violence.

So I want to write about oppression and resistance today. More specifically, I’d like to focus on black women and girls’ resistance to sexual violence.

I have mentioned historian Danielle McGuire’s work on this blog a few times. She wrote an excellent book titled “At The Dark End Of The Street.” I hope that everyone who is interested in women’s history, black history, American history, the history of social movements, and criminal legal issues will read it.

McGuire (2010) writes that black women who were sexually assaulted often spoke out about their experiences and took action on their own behalf:

“Black women did not keep their stories secret. African-American women reclaimed their bodies and their humanity by testifying about their assaults. They launched the first public attacks on sexual violence as “systemic abuse of women” in response to slavery and the wave of lynchings in the post-Emancipation South.”

During the Jim Crow era, women like Rosa Parks took the lead in criminal legal reform related to sexual violence against black women. In reading Devil in the Grove (which I wrote about earlier this week), I came across a reference to letters that black women and their families wrote to the NAACP asking for assistance when they had been raped by white men. Local law enforcement almost never investigated these cases.

I was intrigued about these letters and wrote to the book’s author to ask where he had found the letters that he referenced. He was kind enough to respond to me and to share one particular letter that he found at the Library of Congress. I used the letter as part of a poetry circle that I recently facilitated with young women of color (most of whom were survivors of violence). We read it together, reflected on it, and the young women wrote some powerful poetry in response. Some of the writing prompts that we used included:

1. What if my body belonged to me…

2. I own my body…

3. When I look in the mirror, I see…

As you can imagine the results were both heart-wrenching and heart-enlarging. There were happy and sad tears shed during our circle. The young women have kindly invited me to come back and I look forward to my next visit.

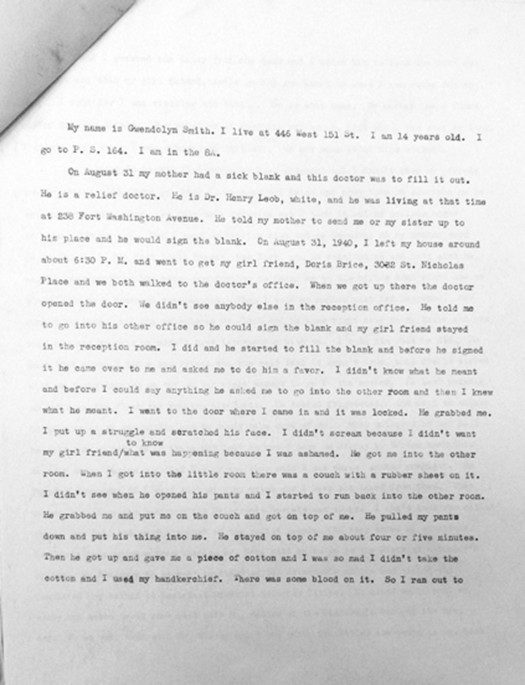

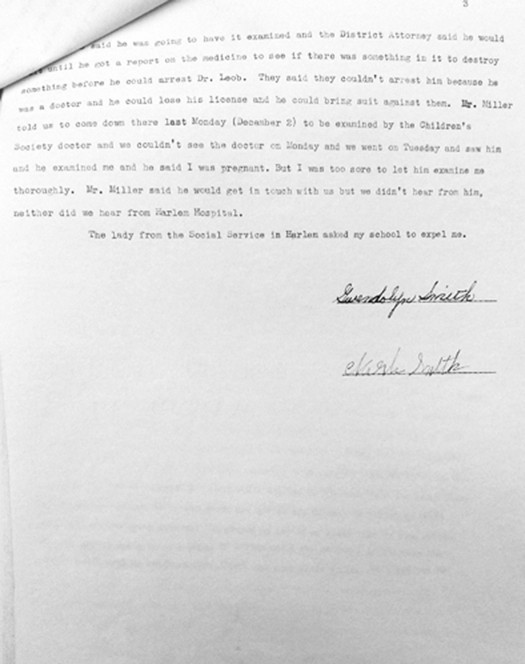

It doesn’t seem fair to talk about the letter without sharing it with you. So I’ll end with the words of 14 year old Harlemite Gwendolyn Smith who bravely wrote to the NAACP in 1940 to tell them about her rape at the hands of a white doctor. The original letter was handwritten and then later transcribed over her signature. Her words illustrate how unsafe it was to be a young black girl in America in the mid-20th century and remind us that it is still unsafe for some black girls in the 21st century. Her story illustrates the institutional violence that young women of color were subjected to in the 1940s: hospitals that were unresponsive, prosecutors who were unhelpful, and social services that were neglectful and ultimately oppressive.

You can read the words of young women from YWEP today & you will hear the echoes of Gwendolyn’s story in their research describing the institutional barriers faced by young women who trade sex for money and survival needs in the 21st century. In other words, there is a discouraging continuity between the experiences of Gwendolyn Smith in 1940 and the oppression still faced by some young women in 2013. Another thing also remains true: Black girls and women have always resisted and continue to do so today…

My name is Gwendolyn Smith. I live at 446 West 151 St. I am 14 years old. I go to P.S. 164. I am in the 8G.

On August 31 my mother had a sick blank and this doctor was to fill it out. He is a relief doctor. He is Dr. Henry Leob, white, and he was living at that time at 238 Fort Washington Avenue. He told my mother to send me or my sister up to his place and he would sign the blank. On August 31, 1940, I left my house about 6:30 P.M. and went to get my girl friend, Doris Brice, 3032 St. Nicholas Place and we both walked to the doctor’s office. When we got up there the doctor opened the door. We didn’t see anybody else in the reception office. He told me to go into his other office so he could sign the blank and my girl friend stayed in the reception room. I did and he started to fill the blank and before he signed it he came over to me and asked me to do him a favor. I didn’t know what he meant and before I could say anything he asked me to go into the other room and then I knew what he meant. I went to the door where I came in and it was locked. He grabbed me. I put up a struggle and scratched his face. I didn’t scream because I didn’t want my girl friend to know what was happening because I was ashamed. He got me into the other room. When I got into the little room there was a couch with a rubber sheet on it. I didn’t see when he opened his pants and I started to run back into the other room. He grabbed me and put me on the couch and got on top of me. He pulled my pants down and put his thing into me. He stayed on top of me about four or five minutes. Then he got up and gave me a piece of cotton and I was so mad I didn’t take the cotton and I used my handkerchief. There was some blood on it. So I ran out to the office and I grabbed the paper from the desk and I asked him to open the door and I ran out and told my girl friend, let’s go and she asked me what I was doing for so long. I told her I was visiting his family. So we went home. My mother has a funny way of knowing things. She asked me if anything was wrong. And why I was gone so long. I didn’t tell her. We got home about nine o’clock.

About September 31 I began to feel sluggish and I didn’t have my periods and my mother took me to Dr. Leob to be examined twice and each time he examined me he said nothing was wrong. He gave me a medicine and I took it and my periods began to come a little bit. But I kept on feeling sick and on November 20 my mother took me to Dr. Bell, 211 West 140th Street, New York, and he examined me and said that he wasn’t sure anything was wrong but for her to bring me to his office that night and he would give me a thorough examination. Then I told my mother what had happened. She almost fainted. and she telephoned Dr. Leob and he came right away to my house and she told him and he said he didn’t have intercourse with me. I told him that he did. He said that maybe I had a boy friend and she said that it wasn’t true, that she is strict with me never leaving me out of her sight except to go to the movies. He kept walking up and down the floor and rubbing his hands. He looked frightened. And said to mother to take me up to his office and he would take care of me. When mother told Dr. Bell he said not to take me up there but that he would take me Friday to Harlem hospital. He took me to Harlem hospital Friday and they said I was three months pregnant. On Tuesday, November 26 I went back with my urine and I have not heard from them. When we got back home the man from the Children’s Society was there. I don’t know who called them. Dr. Bell had sent a report to the relief people. So they asked me questions. We didn’t hear no more from them so Dr. Bell told us to go to the District Attorney’s office. On November 28 we went to the District Attorney’s office and signed the complaint and talked to Assistant District Attorney Titilo. He asked me to tell my story and asked me to come back with Mr. Miller of the Children’s Society the next day. So we went back with Mr. Miller and I had given Mr. Miller the medicine Dr. Leob [___________] said he was going to have it examined and the District Attorney said he would wait until he got a report on the medicine to see if there was something in it to destroy something before he could arrest Dr. Leob. They said they couldn’t arrest him because he was a doctor and he could lose his license and he could bring suit against them. Mr. Miller told us to come down there last Monday (December 2) to be examined by the Children’s Society doctor and we couldn’t see the doctor on Monday and we went on Tuesday and saw him and he examined me and he said I was pregnant. But I was too sore to let him examine me thoroughly. Mr. Miller said he would get in touch with us but we didn’t hear from him, neither did we hear from Harlem Hospital.

The lady from the Social Service in Harlem asked my school to expel me.

Gwendolyn Smith

If you took the time to read Gwendolyn’s letter, I hope that you will share her story with at least one other person. I also hope that you will keep your ears open and listen to the stories of all of the young women who are currently in your lives. When we talk about rape in the public sphere, it is easy to forget that there are millions of us, survivors, who are the ones being discussed and sometimes being re-traumatized. We are human and our stories matter. So, if anyone knows Congressman Gingrey perhaps you can forward Gwendolyn’s letter to him as evidence that some women do in fact get pregnant as a result of being raped. It turns out that the body doesn’t in fact have a magical way of “shutting that down.” At the risk of being presumptuous, I think that I can speak for all rape survivors when I say that we want Akin, Mourdock, Gingrey et. al to STFU instead.

Note: I had the privilege of spending almost 9 years of my life as the primary adult ally for a group of amazing girls & young women called the Rogers Park Young Women’s Action Team (YWAT). Before the organization folded in 2011, the young women and I collaborated on creating a toolkit for engaging young men to address gender-based violence. Interested parties can download that kit here. It’s a shame that Akin, Mourdock, and Gingrey weren’t able to learn about rape culture as younger men. Let’s do better for young men today.