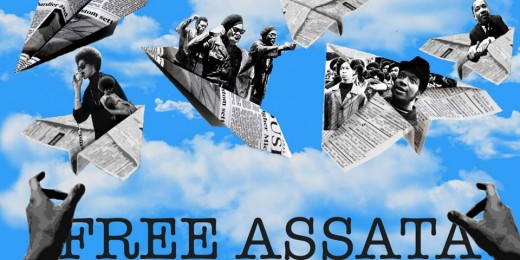

Assata Shakur: Prisoner in the United States (An Interview – Part 1)

This is the testimony of Assata Shakur, formerly JoAnne Chesimard, who was arrested on the evening of May 2, 1973, along with Sundiata Acoli and Zayd Malik Shakur (who was killed by the New Jersey state police). Assata Shakur, who is now in exile, in Cuba, was a member of the Black Panther Party and of the Black Liberation Army. Here she gives testimony regarding her treatment after being captured by New Jersey state troopers. [Source: Still Black, Still Strong: Survivors of the War against Black Revolutionaries. Edited by Jim Fletcher, Tanaquil Jones and Sylvere Latringer (2003)]

Prisoner in the United States (This is only part of the interview, part 2 will be published on Monday)

Assata Shakur: On the night of May 2, I was shot twice by the New Jersey State Police. I was kept on the floor, kicked, pulled, dragged along by my hair. Finally, I was put into an ambulance, but the police would not let the ambulance leave. They kept asking the ambulance attendant: “Is she dead yet? Is she dead yet?” Finally, when it was clear that I wasn’t going to die in the next five or ten minutes, they took me to the hospital. The police were jumping on me, beating me, choking me, doing everything that they could possibly do as soon as the doctors or the nurses would go outside. I was half dead – hospital authorities had brought in a priest to give me the last rites – but the police would not stop torturing me. That went on until the next morning, when I was taken to the intensive care unit. They had to calm down a little while I was there. Then they moved me to another room, which was the Johnson Suite, and they closed off the exit from the hallway. So they could virtually control all traffic in and out. It was just open season on me for about three or four days. They’d turned up the air conditioning so that I was freezing to death. My lungs were threatening to collapse. They were doing everything so that I would get pneumonia.

Q: Did the medical staff participate or acquiesce to this treatment while you were under their care?

AS: Some of them did. The first night there was a doctor who was just as bad as the state troopers. He said: “Why did you shoot the trooper?” – He didn’t know if I had done it or not, but he just jumped on me. Some of the nurses were very supportive; they could really see the viciousness of the police. One of them gave me a call button, so that I could call whenever the state troopers came in my bed. That way I was able to avoid being further beaten up. They had my legs cuffed to the bed, even though I was half dead and my leg was swollen. Some of the nurses protested the way they had my foot cuffed. It was really bleeding and sticking in the flesh.

Q: Is it your opinion that were it not for the medical staff, the police authorities would have murdered you in the hospital with the complicity and compliance of certain doctors.

AS: That’s definitely a possibility.

Q: These members of the medical staff that showed human compassion towards you, were they Black or white, or both?

AS: Black and white. The one who gave me the call button was a German nurse; she had a German accent. Some of the Black nurses sent me a little package of books which really saved my life, because that was one of the most difficult times. One was a book of Black poetry, the other was Siddhartha by Hermann Hesse, then a book about Black women in white America. It was like the most wonderful selection that they could have possibly given me. They gave me the poetry of our people, the tradition of our women, the relationship of human beings to nature and the search of human beings for freedom, for justice, for a world that isn’t a brutal world. And those books – even through that experience – kind of just chilled me out, let me be in touch with my tradition, the beauty of my people, even though we’ve had to suffer such vicious oppression. Those people in that hospital didn’t know who I was, but they understood what was happening to me; and it makes you think that no matter how brutal the police, the courts are, the people fight to keep their humanity, and can really see beyond that.

Q: How long were you at the hospital and how long did your state of medical deterioration last after your capture?

AS: I spent about two weeks at the Middlesex County Hospital. And then I spent another two weeks in the Roosevelt Hospital for the chronically ill. I had two bullet wounds – I still have one bullet in my chest. I was paralyzed in this arm. I had trouble breathing. And after I was released from the second hospital, it took me a couple of years to gain full use of my hand. I was not allowed physical therapy, or medical treatment in the hospital, we had to get a court order for simple things like a rubber ball so I could squeeze my hand and teach myself how to use it again. And the only kind of exercise that I was able to acquire was at the instructions of the nurses. I asked them, what can I do? I was acutely aware that the prison system would do everything possible to frustrate my getting well again. The nurses would give me a towel and even though I couldn’t wring it up, they’d say: “Just try.” So I would put my hand on top of it – and then the police would come and take the towel away, even though I was cuffed to the bed. I don’t know what they thought I was going to do with the towel, but the towel wasn’t the point. The point was to just do everything possible to make me suffer.

Q: So is your experience that you were not given any recuperative or rehabilitative therapy for the wounds that you suffered on May 2, 1973?

AS: I was given some, but I mean the state, the police, the DA’s office, the FBI, I believe, did everything possible to frustrate my recovery.

Q: So you had to get medical therapy as a consequence of legal litigation.

AS: My lawyers went to court and said, she had one arm that’s paralyzed, but I never got physical therapy. We were able to get one team to come in and examine me on one occasion, that was it. The prison doctor would just take my arm and say: ‘Oh it’s perfectly fine, You don’t have a problem.’ And his treatment for most things was laxatives.

Q: After the hospitalization came to an end, were you taken to a detention center or a prison?

AS: Yeah, I was taken to the Middlesex County workhouse. I was put in solitary. A cell which had a door or bars and outside was another big metal door. I was there from June until October-November, when I was taken to the Middlesex County Jail in New Brunswick, and put into a basement, in solitary again. It was a men’s jail, and I was the only woman there. I was kept there until I was taken to New York to go on trial in December, 1973.

Q: You were confined to your cell approximately how many hours a day?

AS: Twenty-four hours a day.

Q: Were you allowed contact visits?

AS: The rules were that you could have contact visits with immediate family and lawyers, but the police kept entering our conversations. They would just ignore the fact that there were supposed to be client-lawyer privileges, or that it was a family visit. They would just be there and nothing we could do about it. Children were not even allowed to visit that prison and it was real sad. You’d just hear the children during the visiting hours screaming their parents’ names, and they would be outside of the prison. You’d just hear these little voices, it was real painful.

Q: Were you aware at the time that there is a law in the U.S. that says that attorneys and clients have a right to confidentiality?

AS: Yeah. My lawyer (and aunt) Evelyn constantly protested the conditions, but she was talking to deaf ears. She went to court I don’t know how many times to have the lawyer-attorney visits respected, with the doors shut, but they were virtually in the room, and that room was bugged anyway.

Q: What do you mean by the term ‘bugged’?

AS: I mean that they had electronic listening devices where we would meet. The guards would come around and say: “We know what you’re saying.” It was their way of saying: “We’ve got it on tape anyway. So what?”

Q: In your view, did the combination of inadequate medical therapeutic attention and the lack of confidentiality with your attorney impede your ability to defend yourself against the many state charges that were subsequently brought against you?

AS: Absolutely. My lawyers had to fight for such elementary things that they couldn’t even deal with the case. The state resisted everything. Most of the energies they would normally be spending preparing for trial, they had to spend filing suits around the right for me to have a ball, to have medical attention, or even have food, which was the worst of any prison that I’ve been in. The women protested the food, it wasn’t just me that they brought this food to, but they said that I was the cause of the protest, even though I was held in solitary confinement and could only speak to the women if I climbed up to the top of the bars and talked out of these little holes. Our whole attempt to prepare for the trial was frustrated on every level.

Q: Did you suffer any disciplinary procedures as a consequence of that protest?

AS: I was already in solitary, so the only thing they could do was just harass me, make my life more difficult.

Q: Did the other women suffer any disciplinary procedure as a consequence of trying to communicate with you?

AS: There were threatened in terms of their court cases; they were told that I was a terrorist…I was accused of killing a New Jersey state trooper and the police claimed that they had to keep me in solitary for my own protection. But the women didn’t believe that. They did every little thing they could to make me feel human.

[Part 2 if the interview will be published here on Monday]