‘Defend Black Women & Die’: Racial Terrorism, Misogyny & Pregnant Silences

I think and write about terrorism against black people. As such, I’ve been very interested in the origins and history of the KKK. Below is an image from 1872 that I came across while doing research about the Klan. I like to examine it periodically. I did so again a few days ago after experiencing another deluge of casual and consistent misogynoir.

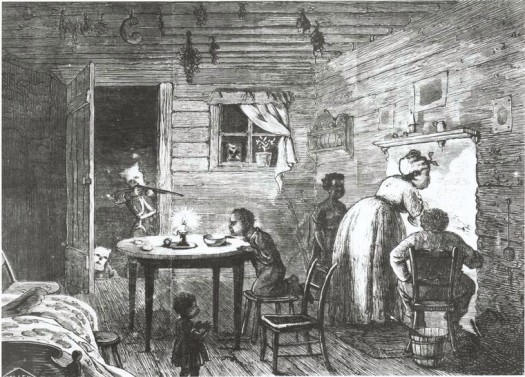

Visit of the Ku-Klux; A drawing by Frank Bellew in Harper’s Weekly, 24 February 1872. (February 24, 1872)

When you look at this image, what do you see? What or who stands out to you? My eyes are immediately drawn to the little girl and older woman who are facing the fire. They dominate the scene, targets of the klansman’s rifle. It appears that he has both of them in his sights. The adult man in the house looks to be seated, he is smaller than the older woman, perhaps she is shielding him from view with her body.

The illustration reminds me of how unprotected black women have been and are. I continue to puzzle through concepts such as “selfhood,” “protection,” and “self-defense” as they might apply (or not) to black people living in the U.S. Years ago, I read an article about a lynching that took place in Georgia in 1919. The article originally published in the Atlanta Constitution was reprinted in the book “Black Women in White America: A Documentary History” edited by historian Gerda Lerner. The title blared “DEFEND BLACK WOMEN — AND DIE! The Lynching of Berry Washington.” From the article:

“On May 24 at 1 o’clock at night, John Dandy and Lewis Evans, white, went down into the colored people’s section of the town and went to the home of a widow by the name of Emma McCollers, who had two daughters. They knocked: but the occupants refused to open the door, and Dandy shot through the door. The ball went through the organ and the machine. That frightened the girls and they ran out to another old lady’s home. Her name was Emma Tisber and is a widow with two little children. The white men went after these colored girls; the girls ran under the porch and hid. These white men broke down the door and tore up the floor. The old widow lady got frightened ran and jumped in the well, and the children screamed for help. Brother Berry Washington, colored, 72 years old, ran out with his shotgun in his hand. When he got near the hall he met both of the white men. John Dandy, 25 years old, with a wife and two children, asked the old man what he came out for. He said: “To see what was the matter with the women and children.” Then John Dandy fired at him and said: “I will kill you, old man.” The old man fired and killed him (John Dandy) first. He fell with his pistol in his right hand and a cigarette in the other, and a flask of — liquor fell out of his pocket. The other fellow ran (Lewis Evans).”

Berry Washington turned himself in to the chief of police on the advice of an acquaintance and was incarcerated. A lynch mob descended on the jail. He was hung to a post and shot to death. The moral of the story was that if you tried to protect black women, you would be severely punished: likely killed. I am certain that these kinds of incidents played out thousands of times across the country. The threat reinforces the idea that black women are inherently violable and that we have no selves that can be defended. Moreover, the threat of “defend black women… and die” was and is integral to racial subjugation and to criminalization. If it is never possible for black women to be defended, than all claims of doing so are inherently illegitimate and all attempts must/will be punished.

It’s worth interrogating how the message ‘defend black women and die’ has been internalized and if it has had a role in complicating black people’s intra-racial relationships. It was 72 year old Berry Washington who came to the defense of widows and children. Where were the younger men? Were they absent because many of them had died or been killed? Were they absent because they’d left for greener pastures? Were they absent because they understood that to come to women’s defense meant likely death for them? If this was the lesson that they learned, what impact would this have had on them? Would they grow to resent their impotence in the face of white terrorism? Would this lead to bottled up anger? Who would then bear the brunt of those emotions?

In some ways, I think that we are still living with the legacy and consequences of this impotent rage. It’s almost impossible to have a meaningful intra-racial conversation about these issues so they fester & remain unattended continuing to harm and hurt everyone impacted. The silences are pregnant with unexpressed hurts, legacies of trauma, and a need for healing. And black women, who are consistently under attack in this country by multiple forces, are left to whisper into the wind: ‘Brothers where are you? Why are we out here on our own?’