No, Mugshots Do Not “Humanize” Anyone…

I collect mugshots. Actually, let me backtrack.

Several years ago, a friend and I were antiquing in rural Virginia. We walked into a store owned by an older white woman. My friend wanted to look at a wood chest that she had spotted in the window. While I waited for her, I browsed the store searching for interesting finds. My friend decided to buy the chest. So I walked towards the cash register as she paid for her purchase. That’s when I saw them.

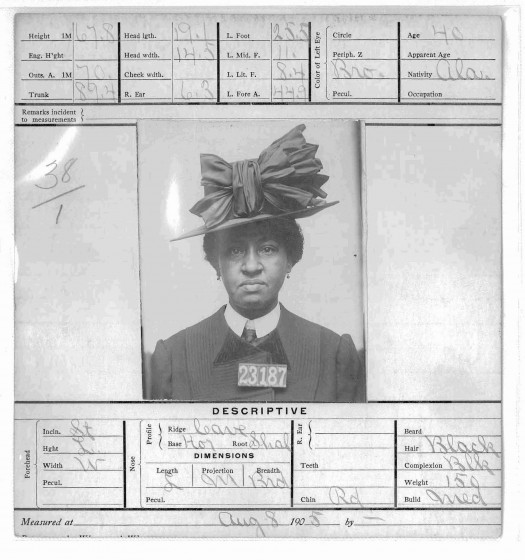

Tucked into the corner was a bin filled with about two dozen Bertillon cards (the precursor of the mugshot). They were all of black men. Some dated back to the 1930s but most were from the 1950s. How did this woman come to acquire these Bertillon cards? Why did she keep them in a bin tucked in a corner of her store? I wanted to ask my questions out loud but thought better of it. Instead, I asked how much she would charge for the lot. She peered at me over her bifocals and said that I could buy all of them for $150. I was surprised. I thought she would charge much more. I wondered again why she had the cards. I bought them; this was in 1998.

Since the late 90s, collecting mugshots has become very popular. They are sold on Ebay, in antique shops, at estate sales and in some cases in art galleries. Depending on the year and quality, some mugshot photos sell for $5 and others can cost over $300. The mugshot is the perfect artifact for the Neoliberal age. The individual in the mugshot is decontextualized from their community and turned into a commodity to be traded and sold in the free market.

I began collecting mugshots because I couldn’t understand why an older white woman in rural Virginia had a couple dozen Bertillon cards of black men in a bin in her antique store. I was unsettled and perturbed so I embarked on my own version of a salvage mission. I fancied myself a rescuer or maybe less generously a savior. For me, these Bertillon cards were mis-placed and I considered destroying them once I brought them home. For weeks which turned into months, they sat in a shoebox at the base of my bedroom closet. I wasn’t curious about the names behind the faces. In fact, it was better not knowing them. I was simply relieved that the Bertillon cards were no longer sitting in that bin in rural Virginia.

Bertillon cards and mugshots are specific creations adopted by the state. They often mark the beginning of the (official) criminalization process and so they are material representations of state power. Both the photograph and the live body depicted become fodder for the criminal punishment system. For many people, the mugshot starts the clock on a dehumanizing journey through an unjust system that can lead to incarceration (where you exist solely as a number).

The mugshot then is a tool used by the state to flatten individuals and turn them into rationalized, bureaucratized ‘things.’ This process is so successful that many observers never consider the pain and suffering (too often) etched on the faces of those being photographed. These images of the accused (usually never convicted) are made public for all to consume as they like. Indeed in the age of the internet, police departments regularly post mugshots on social media. Look at this ‘thing,’ the gatekeepers of the state tell us. And millions of people oblige.

I know that I am not alone in questioning why law enforcement is engaged in such an exchange. Who benefits when they publicly share mugshot photos? Who is harmed? When I was growing up, the Scarlet Letter by Nathaniel Hawthorne was one of my favorite books. Just as Hester Prynne is forced by her neighbors to wear the letter “A” on her chest as punishment and to shame her for having transgressed societal (religious) norms, the police are marking hundreds of thousands of people every year with a Scarlet Letter; In this case, “C” for criminal.

The cops are not in the business of ‘humanizing’ suspects. In fact, their goal is to ‘other’ them and make them alien. The formerly incarcerated and convicted have taken to social media to counter their dehumanization by declaring that they are more than their records. Perhaps the accused will eventually be forced to create a campaign suggesting that they are “more than their mugshots” too.

I never destroyed the Bertillon cards that I bought in 1998. In fact, over the years, when I’d find more, I added them to my shoebox until I eventually transferred the collection to a larger container. The cards and mugshots sat in storage for years until 2012 when I decided to curate an exhibition titled Black/Inside. The original Bertillon cards from my collection were prominently featured. I began the process of telling stories about the flattened lives on those cards. It was another salvage mission but this time I stood as witness & interlocutor rather than as savior.

And every day, I still think about destroying the mugshots because they are intended to dehumanize and oppress… Full stop.

Note: To learn more about the story of the woman on the Bertillon card above, Laura Scott, click here.