Re-Considering Prisoners as “Agents” not “Casualties” of the System

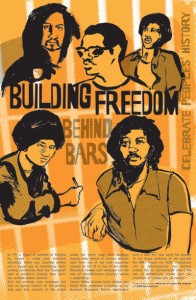

I heard Angela Davis give a presentation at a conference in October. She made many salient points in her critique of mass incarceration but one point stood out in particular. She mentioned that “we talk about prisoners as though they were only the recipients of our charity as opposed to agents in their own rights.” I could not agree more with her characterization.

The histories that have been written about prisoners often treat them merely as “casualties of the system.” It is worthwhile, I believe, to reclaim some of the histories of resistance by prisoners. We just commemorated the 40th anniversary of the Attica prison rebellion in September. I spent a chunk of my summer re-reading a lot of books about Attica and produced (with contributions from some friends) a primer and zine about the uprising. It was my small way of trying to re-insert the idea of prisoner agency and resistance within the stories that we tell about the carceral state. As part of my research about Attica, I came across many incidents of prisoner resistance. One of these took place over the course of three months in 1973 “when prisoners ran walpole.”

In March of 1973, guards decided to walk off the job at Walpole State Prison in Massachusetts. For three months, Walpole was run by prisoners who moved “freely throughout the prison, establishing programs, and democratically determining policy and the structure of their day-to-day lives (p.12).” The prisoners at Walpole were able to successfully self-govern for over three months because they already had the experience of organizing. In 1971, prisoners had established a chapter of the National Prisoner Reform Association (NPRA) at Walpole.

This historical moment is recounted by Jamie Bissonette and her co-authors in their book “When The Prisoners Ran Walpole.” The authors describe the mission and goals of the NPRA:

“The NPRA defined prisoners as workers. Using a labor-organizing model, the NPRA intended to form chapters in prisons throughout the country. The goal of the association was to organize prisoners into labor unions or collective-bargaining units. Prisoners’ unions could then act as a counterbalance to the notoriously powerful guards’ unions in negotiations with prison authorities about how the prisons were run. Prisoners throughout the country began to look at prisoners’ unions as a catalyst for prison reform. But only at MCI Walpole did the NPRA become a recognized bargaining unit, democratically elected by prisoners — the workers — to lead their struggle for reform within the prison.

The NPRA at Walpole remained the recognized representative of the prisoners for two years, and sought State Labor Relations Commission certification along the way. Even after its petition for recognition as a labor union was denied, the NPRA continued to exercise its power as the prisoners’ elected representative for an additional two years (p.11-12).”

For those who are loathe to read books, the history at Walpole is also dramatized in a good documentary titled: “Three Thousand Years and Life.” A couple of clips from the film are below and the whole documentary can be watched on YouTube:

At this historical moment when the Occupy Movement is nascent, it is worth remembering that prisoners are still a marginalized part of the 99%. We need to incorporate the concerns and the needs of prisoners in our calls for economic justice and transformation. The history of prisoner resistance at Walpole points the way.