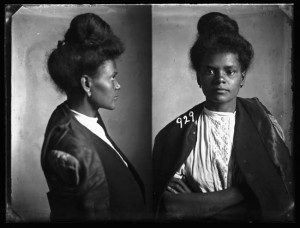

Black Women in Prison in the 19th Century…

Regular readers of this blog know that I have been writing about an early 20th century black woman prisoner named Laura Scott quite a bit. I haven’t written very much about her in the past few weeks as I have been waiting for some court transcripts and other documentation to arrive from California. In the meantime though, I have been reading more generally about the plight of black women prisoners in the 18th and 19th centuries.

You won’t be surprised to know that the numbers of black women prisoners were insignificant until after the Civil War. Almost immediately, existing prisons began to see an increase in the number of former black female slaves. In Illinois for example, in the 1850s, 75% of female prisoners were foreign-born and of the total over 50% were Irish immigrants. In contrast, although black women were only 2% of female prisoners in the late 1850s, they were 25% of all commitments in the five years after the Civil War. By the 1890s, black women represented 2/3 of the daily prison population in Illinois (L. Mara Dodge, 1999). Between 1890 and 1930, the proportion of black women in Ohio state prison increased from 26% to 52%, while the percentage of blacks in the total population of the state rose only from 2% to 3% in the same period. In Tennessee, over 70% of the women committed to the penitentiary in the late 19th century were black (blacks only made up 26% of Tennessee’s population).It is not difficult to understand why this increase occurred. Once black women could no longer be exploited as slaves for their labor, it was easy to incarcerate them and find a new way to lease them out as free labor for corporations and state governments. As Nicole Hahn Rafter (1992) has written about the southern prison system:

“[It] was a form of labor exploitation as well as racial control. States used the growing pool of black convicts to increase public revenues by leasing them to private employers. Black prisoners, both men and women, were forced to participate in the convict lease system, where they faced brutal living conditions and labored long hours at backbreaking field work (p.356).”

Reflecting on the treatment of black women imprisoned in the Midwest and the North, Rafter (1992) suggests that while “racial discrimination was less overt, black women faced harsher punishments for violating the criminal law than did white women. They received higher fines and were more likely to face incarceration than were white women convicted of similar crimes (p.356).”

The stories of female prisoners in the 19th through early 20th centuries have mostly been ignored by historians and social scientists until recently. One of the reasons for this is because their numbers were small relative to male prisoners. Another reason is that these women were seen for the most part as “fallen” women whose lives were not particularly valuable.

A few scholars have begun to reclaim the lost stories of female prisoners of the 19th century. In particular, I recently read an essay by Leslie Patrick (2000) about one of the first female prisoners incarcerated at Eastern State Penitentiary. In 1831, two years after Eastern State Penitentiary was opened, four black women were sentenced to join the 83 men who were incarcerated there. One of these women was a female convict named Ann Hinson who had been convicted of manslaughter. Patrick uses the story of Ann Hinson to illuminate the contradictions that were inherent in the imprisonment of women in the early 19th century. Hinson’s incarceration at Eastern underscored the extent to which female prisoners were neglected in early Penitentiaries. There is hardly any mention of her in official prison documents. What we know about her time at Eastern mostly comes from documentation from an inquiry into some scandals that occurred at the prison during her incarceration there.

Ann Hinson (#100) was sentenced to Eastern for manslaughter and received a two year sentence. Records indicate that she and the other three women who were the first to be incarcerated at Eastern were engaged in cooking and/or washing clothes as part of their daily work. Records and first-hand testimony indicate that Ann Hinson was basically allowed to freely roam through the prison; she was not confined to her cell. She seemed to have become friendly with the underkeeper’s wife, Mrs. Blundin, who had been hired by the prison board to keep an eye on the very small number of women incarcerated at Eastern. Ann Hinson is said to have curried special favors from her and the two of them were accused of having sexual relations with several male prisoners. It is difficult to ascertain whether this portrait of the two women as depraved and immoral is the truth or a figment of the prejudices of the male authors of various reports about the scandals at Eastern Penitentiary. William Griffith, who worked in the shoemaking department, described some of the activities that occurred inside the prison:

“Mrs. Blundin gave a dance party inside the walls. It happened on a night that I was on duty till 10 o’clock. Mr. Wood came up and told me that if I wished to go down and see how they were coming on in the front part of the building, he would spell me awhile — I went down — I found at least thirty persons there, male and female, they were dancing to the music of the violin — a black woman played the violin for them, not an inmate at the Penitentiary — a black woman by the name of Anne, think [sic] No. 100, a convict, was present when I first went down. She appeared to be sitting looking on — dressed in a calico dress with a turban about her head. There was pretty plenty drinking going on — some of the females I found pretty well intoxicated — I saw them drink (Patrick, 2000, p.369).”

These activities seemed to be happening with the full knowledge and consent of the prison warden. They provide an interesting window into an aspect of prison life in the early 19th century. It does seem clear from the available information that Ann Hinson had an unusual amount of “relative freedom” during her incarceration at Eastern. This seems to have derived from her interesting relationship with the prison matron, Mrs. Blundin. If you will recall from a previous post, some white women prisoners at San Quentin in the early 20th century made some similar claims of favoritism for black female prisoners by a prison matron there. I find these contentions endlessly fascinating and it makes me wish that more had been written about the conditions of incarceration for women in prisoners in general but particularly black women in the 19th and early 20th centuries.