About Malcolm X’s Lasting Influence on Prisoners…

I am currently re-reading Eldridge Cleaver’s “Soul on Ice.” This is partly because it’s been a long time since I first read the book and also because of a current project that I am working on. Soul on Ice is a series of letters and essays that paint a portrait of Cleaver’s life before and inside prison. It was written while he was incarcerated for nine years at San Quentin and Folsom prisons. Published in 1968, the book was celebrated for its honesty and hailed as a powerful expression of protest. With Soul on Ice, Cleaver reminds people that just because one is living on the outside of prison doesn’t mean that you are free.

I am currently re-reading Eldridge Cleaver’s “Soul on Ice.” This is partly because it’s been a long time since I first read the book and also because of a current project that I am working on. Soul on Ice is a series of letters and essays that paint a portrait of Cleaver’s life before and inside prison. It was written while he was incarcerated for nine years at San Quentin and Folsom prisons. Published in 1968, the book was celebrated for its honesty and hailed as a powerful expression of protest. With Soul on Ice, Cleaver reminds people that just because one is living on the outside of prison doesn’t mean that you are free.

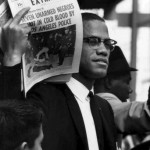

I have written about the special influence that Malcolm X’s story has had in the lives of incarcerated young men. I am reminded of this again in re-reading Cleaver. In the following passage, he explains what drew some black prisoners to Malcolm:

I have written about the special influence that Malcolm X’s story has had in the lives of incarcerated young men. I am reminded of this again in re-reading Cleaver. In the following passage, he explains what drew some black prisoners to Malcolm:

Malcolm X had a special meaning for black convicts. A former prisoner himself, he had risen from the lowest depths to great heights. For this reason he was a symbol of hope, a model for thousands of black convicts who found themselves trapped in the vicious PPP cycle: prison-parole-prison. One thing that the judges, policemen, and administrators of prisons seem never to have understood, and for which they certainly do not make allowances, is that Negro convicts, basically, rather than see themselves as criminals and perpetrators of misdeeds, look upon themselves as prisoners of war, the victims of a vicious, dog-eat-dog social system that is so heinous as to cancel out their own malefactions: in the jungle there is no right or wrong.

Rather than owing and paying a debt to society, Negro prisoners feel that they are being abused, that their imprisonment is simply another form of oppression which they have known all their lives. Negro inmates feel that they are being robbed, that it is “society” that owes them, that should be paying them, a debt.

America’s penology does not take this into account. Malcolm X did, and black convicts know that the ascension to power of Malcolm X or a man like him would eventually have revolutionized penology. Malcolm delivered a merciless and damning indictment of prevailing penology (pp.58-59).

Interestingly, the Autobiography of Malcolm X is still one of the top books that youth in conflict with the law request from me. It seems that the story of his transformation, his personal journey from a kind of mental slavery to an enlightened liberation has resonance for these young people. The Autobiography traces Malcolm’s evolution from a pedestrian street hustler to an internationally renowned leader. Nathan McCall’s memoir “Makes Me Wanna Holler” is another favorite among the young people who I work with. McCall expresses better than I can what appealed to him about Malcolm’s story when he was growing up: “Malcolm’s tale helped me understand the devastating effects of self-hatred and introduced me to a universal principle: that if you change your self-perception, you can change your behavior (p.165).” That captures it perfectly, I think.