Covert Education in the Penitentiary…

This blog is titled “Prison Culture” and yet I write relatively little about the actual culture inside prisons. This is primarily because I have never been incarcerated so I only have an observer’s vantage point from which to address the issue. This is necessarily limiting.

On Monday evening, I spent over two hours listening to Bennie Lee break down the concept of prison culture in the late 1960s into the mid-1970s. I so wish that I had brought a tape recorder with me because his stories were incredibly rich and his knowledge very deep.

As Bennie discussed the prison culture of the 60s and 70s which helped to shape his political and social consciousness, my mind began to race about how to present this information in the upcoming exhibition about the history of black incarceration in the U.S. that I am co-curating. What was clear to me in listening to Bennie is that some black prisoners of the mid-60s through the mid-70s were unique. They were centrally engaged in debates and discussions about incarceration, racism, civil rights, & colonialism that were happening both inside and outside the walls of prisons across the U.S during that era.Bennie spoke about the overt and covert educational groups that prisoners at Stateville and other Illinois prisons organized. As a prisoner, he was steeped in reading books by Khalil Gibran, Don Lee, Malcolm X, Franz Fanon, and more. He recited several oaths of the Conservative Vice Lords, one of which was actually based on Gibran’s “the Garden of the Prophet.” It was mesmerizing and thought-provoking.

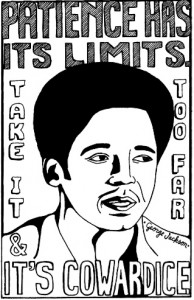

A few months ago, I came across the list of books that were found inside George Jackson’s cell when he was killed at San Quentin in 1971. I was stunned by the sheer number of books but also by the fact that I had only read maybe 30 of them.

Lee Bernstein (2007), who I have quoted several times on this blog, has written about the importance that the ideas of Malcolm X, Angela Davis, and George Jackson had on the consciousness and the writings of a generation of incarcerated people in the 1970s. In writing particularly about Jackson’s influence, Bernstein (2007) suggests that:“To prisoners, Jackson was as much a teacher of radical political philosophy and spokesperson for a crisis behind bars as symbol of oppression. His education behind bars and uncompromising politics would come to serve as a model for prisoners (p.312).”

According to Bernstein during the late 60s and early 70s, there existed a “covert — unofficial and strategically hidden from authorities — education system that thrived in American prisons (p.312).” Bennie spoke to this and insisted that elder prisoners would compel younger inmates to “get an education” while locked up. In fact, this became enshrined in the codes of conduct of various gangs inside prisons. Refusing to participate in educational groups would mean that you were bringing dishonor on your gang and for this one could be punished.

Last year, while I was writing about the Attica Prison Uprising, I suggested that covert and informal educational groups helped to lay the groundwork for the rebellion. During the summer of 1971, prisoners at Attica launched peer-led classes in sociology. This was preceded by the formation of several study and discussion groups led by prisoners who had affiliations with the Nation of Islam, the Black Panther Party, the Young Lords and the Five Percenters. Attica prisoner Carl Jones-EL explained:

“The education department, the school system that they have, it only goes so far, far as trying to give a man an education. We more or less have to educate ourselves. When we came here [Attica] we knew the conditions and we felt that people should come together and get a better understanding of the conditions here, what was being did to them by the administration. So behind this we would hold meetings in the yard. We’d hold open house and whoever wanted to come and listen to our political ideology were welcome. We didn’t bar anyone. This was frowned upon by the institution and they would break it up. If we congregated too big, this wasn’t allowed. In order to reach everyone, we had to set up some sort of communications. We had to get along with the different factions here: the Muslims, the Fiver Per-centers, and all the other factions to become one solid movement, rather than just be separate parts here trying to accomplish the same things, better conditions for the inmates. (2)”

These informal gatherings provided a forum for prisoners to debate and discuss the social and political issues of the day. The McKay Commission found that these prisoner-created spaces politicized and radicalized inmates and contributed to a series of protests in the summer of 1971.

It is important not to romanticize this period since it is clear that most prisoners in the 60s and 70s were no more politicized than the general population. There was however a cadre of incarcerated people who had a revolutionary political orientation and it is important to reclaim that history if we are to fully understand the American prisons of the 20th century.