They Came for the Japanese Too…

Earlier this week, I read an article in the New York Times about the pilgrimage of over 400 Japanese Americans to Tule Lake, the site of a camp where over 18,000 of their ancestors were incarcerated during World War II.

Earlier this week, I read an article in the New York Times about the pilgrimage of over 400 Japanese Americans to Tule Lake, the site of a camp where over 18,000 of their ancestors were incarcerated during World War II.

There were 10 internment camps in the U.S. during the war and over 120,000 Japanese Americans were incarcerated in them. The history of the Tule Lake camp is particularly interesting because of who was interned there:

In early 1943, about a year after Japanese-Americans were rounded up into the camps, the American authorities, seeking Japanese language speakers in the military, distributed a loyalty questionnaire to all adults. Question No. 27 asked draft-age men whether they were willing to serve in the armed forces. No. 28 asked whether detainees would “swear unqualified allegiance to the United States” and “forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, or any other foreign government.”

Anything except a simple “yes” to the two questions meant relocation to Tule Lake, which became the most heavily guarded of the camps. Army tanks were stationed here, reinforcing the security provided by 28 guard towers and a seven-foot-high barbed wire fence.

Osamu Hasegawa, 90, recalled that his parents answered “no” after a heated family debate. Because his parents were born in Japan — Japanese immigrants were not allowed to become American citizens until 1952 because of discriminatory immigration laws — they feared that forswearing allegiance to the country of their birth would render them stateless while Mr. Hasegawa and his American-born siblings remained in the United States.

After his parents answered “no,” Mr. Hasegawa became one of the nearly 6,000 Japanese-Americans at Tule Lake to renounce their American citizenship.

I have to admit to being fairly ignorant about the history of Japanese internment in the U.S. and Canada during World War II. I shouldn’t be so clueless but I learned nothing about this part of American history in school (middle or high school or college). I suspect that I am not alone in my lack of knowledge about this chapter in history. Next year, I plan to begin a course of independent study about Japanese Internment. I have no doubt that I will be sharing a great deal of what I learn here on the blog.

In the meantime, I was moved by the story of Norman Mineta who spent 21 years in Congress. He shared his story of being 10 years old when Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941. As a Japanese American, he and his family were interned in a camp:

We had just come home from church when the phone started ringing. My dad was a leader in the Japanese-American community in San Jose, and people started calling to ask if we had heard about the attack that day on Pearl Harbor. We were all stunned. I’ve only seen my dad cry three times, and that day there were tears in his eyes. He loved America and had come to the United States when he was 14. He couldn’t understand why the land of his birth was attacking the land of his heart. That same day, Dec. 7, the FBI came. From behind our house we heard a neighbor’s child yelling, “The police are taking Papa away.” By the time my dad ran over there, the FBI had arrested his friend, the head of the Japanese American Association. His family didn’t hear from him for six months. The Buddhist priest was next. They were taking only community leaders. And this upset my dad, because he was not arrested. But he was close to the sheriff and the city manager and they probably told the FBI that he was OK.

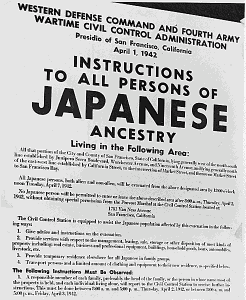

The evacuation order came on Feb. 19, 1942. Big placards were put up, telling all those of Japanese descent, “alien and non-alien,” that they would have to leave their homes for an unknown distant barracks. We lost our homes, we lost our businesses, we lost our farms, but worst of all, we lost our most basic human rights. Our own government had branded us with the unwarranted stigma of disloyalty. We were put under a curfew, from 7 p.m. to 7 a.m. There was a lot of panic. People who came to our house to see my dad were crying and wondering what was going to happen. In late January, my dad called all the family together. I was 10. He said, “I don’t know what is going to happen to your mother and me, but all of you are American citizens. Always remember this is your home.” Source: The Camps at Home. by Mineta, Norman, Newsweek, 00289604, 3/8/1999, Vol. 133, Issue 10

I can’t wait to delve further into this history. I am particularly interested in learning about those who resisted this injustice. I also want to know whether the civil rights organizations of the time spoke out against this injustice or were they silent? If they didn’t speak out, why not? I look forward to sharing what I find out with you in the coming months.