Last night, I was privileged to attend an event titled “Breastfeeding and Incarceration: A Panel Discussion on Maternal Rights in Prison and Criminalization of Black Mothers” organized by the Chicago Alliance to Free Marissa Alexander (CAFMA), Moms United against Violence and Incarceration and Black on Both Sides. It was a wonderful, infuriating, and moving event.

breastfeeding & incarcerated mothers panel (photo by Sarah Jane Rhee, 6/26/14)

My friend Ayanna Banks Harris who is a co-organizer of CAFMA was on the panel. I thought that her remarks were excellent and asked for permission to publish them. They are below for all of you to read and consider. My thanks to Ayanna for allowing me to share her words here.

Breastfeeding & Incarcerated Mothers

Remarks by Ayanna Banks-Harris

26 June 2014

I am very grateful for this opportunity to share the stories of two mothers who are just a miniscule representation of the thousands of mothers whose stories go untold and voices go unheard.

Before our discussion opens to insuring breastfeeding rights of mothers who are incarcerated, we must examine how and why our society is caging mothers at increasingly exponential rates and why we’ve become comfortable with so many children being ripped from the loving care of their mothers who are more often than not nurturing, loving, caring and providing.

Exactly four years ago, a pregnant woman and already mother of two fled the marital home she shared with her second husband as she had been physically abused multiple times by him. Being pregnant did not ward off the violent attacks of her husband, the father of her unborn child. Six weeks prior to her scheduled delivery date, she gave birth to a daughter who would remain in NICU for weeks following her birth. Nine days post-partum, the now mother of three was once again attacked and threatened and has been in a battle for the right to live her life freely ever since.

She is Marissa Alexander.

In August 2010, just nine days after giving birth, Marissa briefly left her daughter’s side to return to her marital home to retrieve necessary documents at a time she knew her estranged husband wouldn’t be home. While there, he did return home along with two of his children from another relationship and began invading her privacy by going through her phone. In a jealous rage, he confronted her while she was in the restroom, assaulted her, shoved her, strangled her, threatened her and held her against her will preventing her from fleeing. Once she was able to leave, she headed to the garage where her car was parked but left behind her keys and phone.

Upon realizing she’d left her keys and she attempted to open the garage door but could not.

Trapped, she retrieved her gun for which she has a permit and re-entered the home with her gun down at her side for the sole purpose of obtaining her phone and keys and leaving through another exit.

Upon hearing her reenter the home, her estranged husband entered the kitchen. He became further enraged upon seeing the weapon at her side, lunged at her while yelling, “Bitch, I will kill you.” It was at the moment of him lunging at her did Marissa raise her arm with weapon in hand to fire one shot in an upwards direction that neither hit him nor anyone else. Marissa was charged with three counts of aggravated assault with a deadly weapon, each of which carries a mandatory minimum sentence of 20 years.

Marissa went from asserting her right to live by defending herself against her husband to asserting her right to live by defending herself in a fight against a system that seeks to imprison her for 60 years for interrupting the violence inflicted upon her.

Marissa Alexander is just one of thousands of women who are incarcerated for warding off abusive partners as violence inflicted against women and girls puts them at greater risk for incarceration because their survival strategies are often deemed criminal.

Domestic violence is just one precipice from which mothers, specifically those of color, fall into the criminal justice system

Earlier this year, another mother of three had to make a decision no mother, no person should have to – leave her children in the car that she could attend an interview that would catapult her and her family out of homelessness (housing insecurity) and poverty or be a no-show.

It’s not that Shanesha Taylor hadn’t diligently coordinated the day so that she wouldn’t have to make such a decision as she had already arranged a caretaker for her two youngest children. When she arrived at the home of the caretaker on her way to the interview, no one answered the door. Literally having no other options, Shanesha made the difficult decision to leave her kids unattended in the car for an hour. She made every attempt within her power to alleviate the dangers involved with doing so – cracking the tinted windows and leaving keys in the ignition with the engine off but allowing the fan to continue to blow air. Upon returning to the car following her interview – an interview she says went extremely well and resulted in a job offer – Shanesha discovers her car is parked in the center of a crime scene. The two children who were in the car were taken to the hospital and were immediately released as they had not been harmed. Shanesha was arrested and charged with two counts of felony child abuse. Though only two of her children were in the car, both unharmed, all three of her children have been removed from her custody. She faces upwards of seven years in prison.

What is solved by imprisoning Shanesha for seven years?

What is solved by caging Marissa for 60 years?

How are these families, these children, made better by their mothers being incarcerated?

How are our communities any safer as a result?

Why is such behavior even deemed criminal?

Though the manner in which Marissa and Shanesha were catapulted into the judicial system and separated from their children are vastly different, a similarity is glaring -both of these mothers, women of color, have been incarcerated, face years of further incarceration, are no longer their children’s primary caretaker/guardian not for having actually done harm, not for having an intent to do harm, but because of a hypothetical harm that COULD HAVE been done. We are punishing mothers in desperate situations against impossible odds for NOT inflicting harm on their children or others.

It is past time that we demand to live in a society that is less concerned with being punitive for every reaction and obsessed with ensuring solutions for all, that no person – no mother – is cornered in perilous situations with no options.

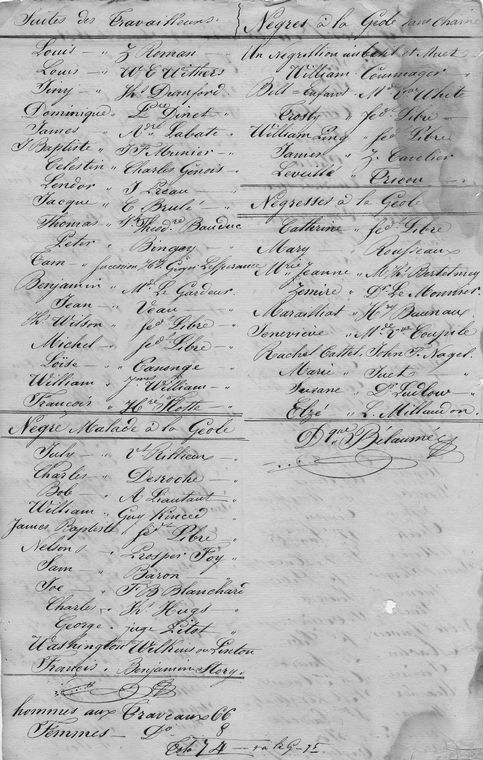

![[Report on employment of slaves in public works and chain gangs. Top reads 'Rapport du 23 aux 24...'.] (February 23-24, 1824)](https://www.usprisonculture.com/blog/wp-content/uploads/2013/11/chaingangdoc.jpg)