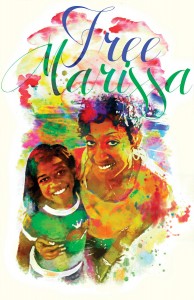

Guest Post: On Marissa Alexander and the Politics of Defenseless Defense

I read a version of this post as a working paper. I was browsing the internet and came across it. I wrote to the paper’s author who graciously shared her work. After reading it, I asked if she’d allow me to post a version of her paper on this blog. She agreed and below is an edited version of her argument. I am grateful to Jasmine for allowing me to share this post with you. Don’t forget that this is the week of action to free Marissa Alexander. Details are here. Also, if you can, please donate to her legal defense here.

On Marissa Alexander and the Politics of Defenseless Defense[i]

by Jasmine Montgomery

This is my life I’m fighting for. This is my life. And it’s my life, and it’s not entertainment. This is my life. If you do everything to get on the right side of the law, and it’s a law that does not apply to you, where do you go from there?

Marissa Alexander spoke these words in a 2011 interview shortly after her sentencing. For a long time, they were the only access a public confronting the injustice of her case had to Alexander’s voice, thoughts, suffering, and resistance to the denial of her right and her truth — from the rejection of her pretrial motion seeking immunity from prosecution through the appellate court’s affirmation of the pretrial judgment and reversal of the trial judgment and the subsequent, months-long struggle over her pre-trial release. It’s from a position of believing and listening to Alexander that our political mobilizations to defend and free her, to advance an analysis of relations and structures of power that produce vulnerability, and to imagine a world transformation in which racial justice is possible take flight.

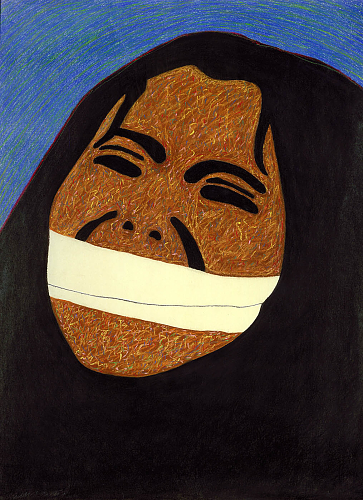

Alexander’s statement itself is the expression of a knowledge and politics in excess of the liberal reforms its various reproductions have been used to support. In this statement, Alexander is not asking to be identified as an innocent victim who has been treated unfairly by a fundamentally or even potentially just criminal legal system. She is instead fundamentally questioning what can be done in a society that originated as a slave democracy — a society whose foundational violence produces the structural position of blackness, which is constituted by and as indefensibility. There are two sides of the law: the right and the wrong; and Alexander has always been captive on the wrong side. No matter what she did, the law did not apply to her.No matter the volume of officially documented evidence of abuse, or the active injunction of protection against domestic violence. No matter the “normative value” of her marital status, socio-economic status, and educational attainment. And no matter Alexander’s own recounting of the violence she experienced and the fear she felt on that day and many others, the judge overseeing her pretrial hearing reasoned that there was “insufficient evidence that the Defendant reasonably believed deadly force was needed to prevent death or great bodily harm to herself,” because Alexander did not show visible signs of serious bodily injury and her actions — re-entering the house with a gun rather than exiting through the front, back, or garage door — were “inconsistent with a person who is in genuine fear for her life.” No matter the lack of evidence disputing Alexander’s claim that she could not have safely exited her home; or the fact that Stand Your Ground explicitly stipulates no duty to retreat.