It’s domestic violence awareness month. I’ve been wanting to write about this all month. Sadly, between work and life, I’ve had little time to post regularly. I hope that 2016 will allow me to do so more consistently.

As some of you know, I was a co-founder and co-organizer of the Chicago Alliance to Free Marissa Alexander (CAFMA). CAFMA has become Love and Protect. The mission of Love and Protect is to “support those who identify as women and gender non-conforming persons of color who are criminalized or harmed by state and interpersonal violence.”

This month, in partnership with other defense committees and organizations, Love and Protect launched a project called #SurvivedandPunished.

#SurvivedandPunished released its vision statement last week. I am republishing it below:

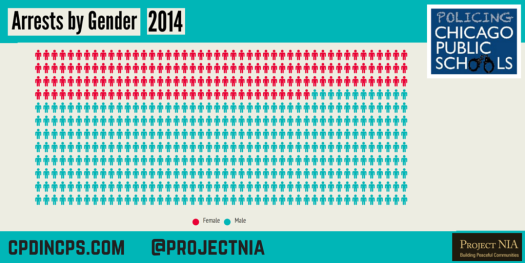

For many survivors, the experiences of domestic violence, rape, and other forms of gender violence are bound up with systems of incarceration and police violence. According to the ACLU, nearly 60% of people in women’s prison nationwide, and as many as 94% of some women’s prison populations, have a history of physical or sexual abuse before being incarcerated. Once incarcerated or detained, many women (including trans women) and trans & gender non-conforming people experience sexual violence from guards and others. Being controlled by police, prosecutors, judges, immigration enforcement, homeland security, detention centers, and prisons is often integrated with the experience of domestic violence and sexual assault. This is especially true for Black, Native, and immigrant survivors. The Survived And Punished Project demands the immediate release of survivors of domestic and sexual violence and other forms of gender violence who are imprisoned for survival actions, including: self-defense, “failure to protect,” migration, removing children from abusive people, being coerced into acting as an “accomplice,” and securing resources needed to live. Furthermore, we demand that these same survivors are swiftly reunified with their families.

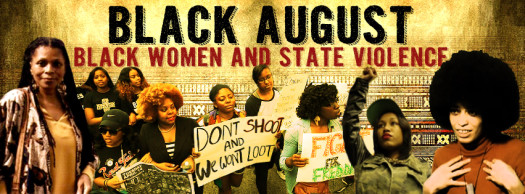

Our coalition of freedom campaigns and organizations believes that policing, immigration enforcement and the prison industrial complex are violent institutions that primarily target poor communities of color. They are fundamentally racist, anti-family, anti-trans/queer, anti-woman, anti-Black, anti-Native, anti-poor and anti-immigrant. Black women are constantly policed, controlled, and dehumanized by these systems. Immigrant and refugee survivors face constant threat of detention and deportation. Native women’s high rates of incarceration are part of the colonial conditions of ongoing gender violence waged against them. Trans women, trans, & gender non-conforming people are violently profiled and targeted by police officers and prison guards. All are threatened with being separated from their children and families. Poverty, which disproportionately impacts communities of color and trans/queer communities, renders survivors even more vulnerable to all forms of violence, including police violence and imprisonment. It is in this context that self-defense and other survival actions are often criminalized.

“GOOD VICTIM” VS “NON-VICTIM CRIMINAL”

In the face of epidemic rates of domestic and sexual violence, anti-violence advocates have partnered with police and district attorneys to try to find protection for survivors, and to institutionalize gender violence as a “crime.” However, this pro-criminalization approach to addressing violence has created a racial divide between “good victims” and non-victim “criminals.” A “good victim” is one who readily accesses and cooperates with the criminal legal system in order to prosecute and incarcerate their batterer or rapist. But when a survivor of sexual or domestic violence is only supported when seen as a “victim of crime,” survivors who are already criminalized are not recognized as people in need of support and advocacy. Survivors are criminalized for being Black, undocumented, poor, transgender, queer, disabled, women or girls of color, in the sex industry, or for having a past “criminal record.” Their experience of violence is diminished, distorted, or disappeared, and they are instead simply seen as criminals who should be punished. They face hostility from police, prosecutors and judges, and they are often denied the support “good victims” receive from anti-violence advocates. These “criminal” survivors are then particularly vulnerable when racist pro-criminalization policies (such as mandatory minimums, the war on drugs, “Felons not Families” deportation enforcement, and increased police authority) are waged against our communities because those policies facilitate and reinforce domestic and sexual violence. For example:

Marissa Alexander defended her life from her abusive husband by firing one warning shot that caused no physical harm. She was targeted by a racist smear campaign by Florida State Attorney Angela Corey designed to frame her as an “angry black woman,” but never as a victim of domestic violence. She was prosecuted and sentenced to a mandatory minimum of 20 years in prison.

When Marcela Rodriguez called the police during a domestic violence incident, the police came, arrested her, and turned her over to Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE), which detained her and forced her into deportation proceedings.

Nan-Hui Jo fled her abusive American citizen partner with her child to seek safety for her and her young daughter. She was then arrested for child abduction, and the district attorney who prosecuted her tried to portray her as a manipulative illegal immigrant seeking to cheat U.S. systems, calling her a “tiger mom” who was too competent to be a victim.

The New Jersey 4 were called a “killer lesbian gang” by both prosecutors and media after they defended themselves against racist, misogynistic and homophobic sexual violence in a gentrified neighborhood.

Ky Peterson was told that he, as a transman, was not a “believable victim” of rape after defending himself against a brutal sexual assault, and he was bullied into signing a “plea deal” of 20 years in prison.

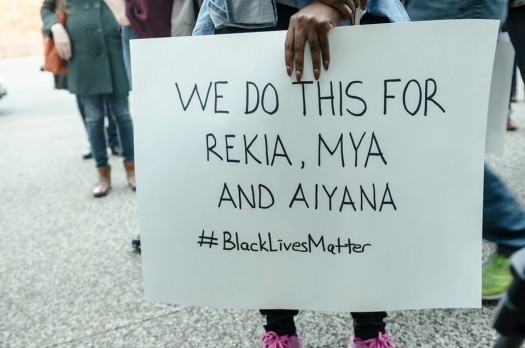

All of these survivors of violence were prosecuted using racist, sexist, anti-trans/queer and classist logic. Many were prosecuted by using policies that target poor communities of color, and many did not receive support from anti-violence organizations. The same system that criminalizes, re-traumatizes and further abuses victims is also the one that the anti-violence movement entrusts and authorizes to protect survivors and create safety. The institutionalization of this racialized “good victim/criminal” dichotomy has left a huge portion of survivors, overwhelmingly Black women, unsupported and unaccounted for by the anti-violence movement.

WHERE DO WE GO FROM HERE?

We affirm the lives and self-determination of all survivors of domestic and sexual violence. We endorse efforts to abolish these anti-survivor systems and create new approaches that prioritize accountable, community-based responses to domestic and sexual violence. Knowing that abuse and incarceration are both meant to isolate and diminish the person, we hope for more restorative resources and options for survivors. We must organize for a world in which survivors are always supported by their communities. We look forward to the day when survivors do not have to resort to calling 9-1-1, anonymous hotlines, restrictive shelters far from home, and broken legal systems in their attempts to find support. We reject false dichotomies of “good victim/prisoner/immigrant” and “bad victim/prisoner/immigrant” that individualize the problems of domestic and sexual violence, and choose to instead target the systemic issues that further facilitate abuse. We focus on survivors because we want to highlight the specific pipeline between surviving sexual and domestic violence and being arrested, locked up, and/or deported.

We call for the anti-domestic violence and anti-rape movements to seriously contend with how their enmeshed relationships with prosecutors and police limits the ability to see criminalized victims as deserving of resources and advocacy, undermining their safety and well-being. We call for racial justice and migrant justice movements organizing against the violence of policing, immigration enforcement, and prisons to consistently highlight survivors of gender violence in political analysis and strategies. We call for your fearless support of survivors who live within the intersection of gender violence and criminalization. They need and deserve our solidarity.