Dr.King’s Fear of Solitary Confinement and Bradley Manning

I have received a couple of e-mails from readers of this blog sharing information about the Bradley Manning case. Reportedly this military officer at the heart of the Wikileaks scandal is being held in solitary confinement. I have previously blogged about my belief that solitary confinement is torture.

I am a student of history. I think that we have a lot to learn from our past in the continuing struggle for social justice. I have read extensively about the life of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. I read his autobiography while I was in high school. His experiences have a direct bearing on the current debate about solitary confinement as an instrument of torture.

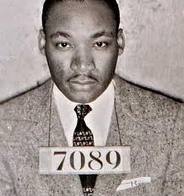

In 1963, Dr. King moved the site of the civil rights struggle to Birmingham, Alabama, a manufacturing city and one of the richest in the South. The two-month campaign was as rough and as risky as King had anticipated. Hundreds were arrested. An injunction was granted forbidding marches and demonstrations, but King decided to break it. He dressed in denims and a workshirt – his jail clothes — and led a march on Good Friday, April 12, 1963. Again he was arrested, this time placed in solitary confinement.

Historian Adam Fairclough (1995) writes about this incident in his book Martin Luther King Jr:

King dreaded solitary confinement. Separated from Abernathy after his arrest on April 12, “those were the longest, most frustrating and bewildering hours I have lived,” he remembered. “You will never know the meaning of utter darkness until you have lain in such a dungeon, knowing that sunlight is streaming overhead and still seeing only darkness below.” A gregarious man, he hated being alone. He ached to see his new daughter, born a few days earlier. He worried about the bail money. And he experienced straightforward fear. (p.77)”

It’s worth hearing about this entire episode in Dr. King’s own words. From the Autobiography of Martin Luther King, Jr:

We rode from the motel to the Zion Hill church, where the march would begin. Many hundreds of Negroes had turned out to see us and great hope grew within me as I saw those faces smiling approval as we passed. It seemed that every Birmingham police officer had been sent into the area. Leaving the church, where we were joined by the rest of our group of fifty, we started down the forbidden streets that lead to the downtown sector. It was a beautiful march We were allowed to walk farther than the police had ever permitted before. We were singing, and occasionally the singing was interspersed with bursts of applause from the sidewalks.

As we neared the downtown area, Bull Connor ordered his men to arrest us, and somebody from the police force leaned over and reminded Mr. Connor, “Mr. Connor, we ain’t got nowhere to put ’em.” Ralph (Abernathy) and I were hauled off by two muscular policemen, clutching the backs of our shirts in handfuls. All the others were promptly arrested. In jail Ralph and I were separated from everyone else and later from each other.

For more than twenty-four hours, I was held incommunicado, in solitary confinement. No one was permitted to visit me, not even my lawyers. Those were the longest, most frustrating and bewildering hours I have lived. Having no contact of any kind, I was besieged with worry. How was the movement faring? Where would Fred and the other leaders get the money to have our demonstrators released? What was happening to the morale in the Negro community?

I suffered no physical brutality at the hands of my jailers. Some of the prison personnel were surly and abusive, but that was to be expected in Southern prisons. Solitary confinement, however, was brutal enough. In the mornings the sun would rise, sending shafts of light through the window high in the narrow cell which was my home. You will never know the meaning of utter darkness until you have lain in such a dungeon, knowing that sunlight is streaming overhead and still seeing only darkness below. You might have thought I was in the grip of a fantasy brought on by worry. I did worry. But there was more to the blackness than a phenomenon conjured up by a worried mind. Whatever the cause, the fact remained that I could not see the light.

When I had left my Atlanta home some days before, my wife, Coretta, had just given birth to our fourth child. As happy as we were about the new little girl, Coretta was disappointed that her condition would not allow her to accompany me. She had been my strength and inspiration during the terror of Montgomery. She had been active in Albany, Georgia, and was preparing to go to jail with the wives of other civil rights leaders there, just before the campaign ended.

Now, not only was she confined to our home, but she was denied even the consolation of a telephone call from her husband. On the Sunday following our jailing, she decided she must do something. Remembering the call that John Kennedy had made to her when I was jailed in Georgia during the 1960 election campaign, she placed a call to the President. Within a few minutes, his brother, Attorney General Robert Kennedy, phoned back. She told him that she hay learned that I was in solitary confinement and was afraid for my safety. The attorney general promised to do everything he could to have my situation eased A few hours later President Kennedy him self called Coretta from Palm Beach, and assured her that he would look into the matter immediately. Apparently the President and his brother placed calls to officials in Birmingham; for immediately after Coretta heard from them, my jailers asked if I wanted to call he: After the President’s intervention, conditions changed considerably.

I wanted to highlight Dr. King’s experience with solitary confinement to provide more testimony about the horrific nature of being held in isolation. I wanted convey the sense of fear and hopelessness that is nothing less than actual torture. I hope that as people think about Bradley Manning and the millions of other people across the globe currently being isolated in this way, that they will think about Dr. King’s words. We must do better than this. We must reclaim our humanity.

NOTE:

Prison Culture will be on hiatus for the next couple of days as I focus on the stack of work that I have to get through. I am very grateful to all of the readers who stop by this blog and also to those who reach out to me via e-mail. Your e-mails often provide the inspiration for the posts that I write. So thank you.