Prisoner Reentry as ‘Myth’: Lessons from Michael Vick

The recent controversy over Michael Vick has reaffirmed what I have been saying for what seems like an eternity…

In the U.S., the concept of prisoner reentry is a hoax and a form of symbolic violence. Michael Vick was cruel to dogs. That is a terrible thing to be sure. But for this transgression, Tucker Carlson calls for him to be executed? Some people will dismiss this comment as a rant from a right-wing nut job. I think that this is wrong. I believe that Carlson was articulating a truth about how many Americans feel: If you are a prisoner in the U.S. (particularly if you are black or brown), society would prefer that you disappear for life. If the state doesn’t kill you, hopefully the streets will.

In the past couple of days, I have read blog posts from individuals (some of whom call themselves progressives) who ‘worry’ that people who favor allowing Vick to claim a life after incarceration are actually “condoning” Vick’s actions. WTF? Who the heck is condoning the torturing of animals?

Vick already served almost two years in prison for his crime. This is more than can be said for most of the banksters on Wall Street who tanked the economy and have harmed millions of people across the globe as a result. Look I am against prisons so I am not advocating locking up Vick or the banksters. I am simply making the case that only certain people go to prison and those people are mostly black, poor, and male. Vick fits two out of those three criteria while the banksters fit none.

Sociologist Loic Wacquant (2010) offers a provocative take on the concept of reentry in an upcoming article titled “Prisoner Re-Entry as Myth & Ceremony.” The article advances a number of ideas including debunking the concept of the prison industrial complex. I am not going to address myself to Dr. Wacquant’s critique of the PIC in this post. For those interested in his thoughts on that, you can read a previous post here.

Today, I will focus in particular on some of his arguments about so-called prisoner “reentry.” Two important points stand out to me from his article. First, he makes the case that “most released convicts experience not reentry but ongoing circulation between the prison and their dispossessed neighborhoods.” Anyone who has worked with former prisoners can attest to this reality. Michael Vick’s situation is anomalous from other former prisoners because even though he lost all of his money while incarcerated, he still had a rare talent that could be monetized upon his release. This is not the case for 99.9% of the other people who are released from prison each year. Instead most former prisoners find themselves struggling to overcome legal, social, and economic obstacles upon their release. For most, the obstacles prove to be insurmountable and they return to prison. Incidentally, Wacquant makes the salient point that most former prisoners were actually members of a marginalized group “that was never socially and economically integrated to start with.” For that group, it means that the concept of reentry is a misnomer.

The next important point that I want to underscore from Wacquant’s article is focused on the way that reentry actually serves to reinforce state control over the lives of former prisoners. Wacquant (2010) writes: “Reentry outfits are not an antidote to but an extension of punitive containment as government technique for managing problem categories and territories in the dualizing city.” In their focus on the individual and on the bureaucratic management of individual problems, reentry programs actually serve as part of the apparatus of state control over the lives of former prisoners. In other words, Wacquant contends that reentry programs “are not a remedy to, but part and parcel of the institutional machinery of hyper-incarceration.” This is an important and troubling insight for all of us who focus on these issues.

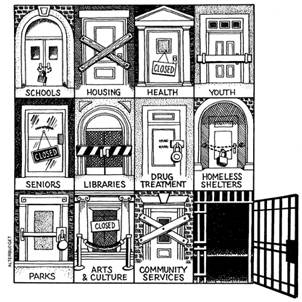

I mentioned at the beginning of this post that the concept of reentry is a form of symbolic violence. What I mean by this is that reentry is actually a mirage. It is out of reach because as a society we are not serious about actually reintegrating former prisoners. We pay lip-service to this idea but we don’t do what would be necessary to lay a foundation to ensure successful reintegration. Here Wacquant doesn’t hold back in exposing the hypocrisy of this matter. I am going to quote a long section of the article because it lays bare the fallacy of the concept of reentry in the best way that I have seen to date.

[T]he so-called “reentry movement” is but a minor bureaucratic adaptation to the glaring contradictions of the punitive regulation of poverty. Proof is its measly funding: the Second Chance Act of 2008, ballyhooed by the bipartisan political coalition that passed it and the scholars it subsidizes has an annual budget of $165 million equal to less than one-quarter of one percent of the country’s correctional budget. Put differently, it provides the princely sum of $20 monthly per new convict released, enough to buy them a sandwich each week. If the authorities were serious about “reentry,” they would allocate twenty to fifty times that amount at minimum.

They would start by reestablishing the previously existing web of programs that build a bridge back to civilian life — furloughs, educational release, work release, and half-way houses — which has atrophied over the past two decades and avoid locating “reentry services” in decrepit facilities located in dangerous and dilapidated inner-city districts rife with crime and vice (Ross and Richards 2009).

They would restore the prison college programs that had made the United States an international leader in higher education behind bars, until convicts were denied eligibility for Pell Grants in 1994 to feed the vengeful fantasies of the electorate, even as government studies showed that a college degree is the most efficacious and cost-effective antidote to reoffending (Page 2004). They would end the myriad rules that extend penal sanction far beyond prison walls and long after sentences have been served — such as the statutes barring “ex-cons” from access to public housing, welfare support, educational grants, and voting — and curtail the legal disabilities inflicted on their families and intimates (Comfort 2007).

They would restrain and reverse the runaway diffusion of “rap sheets” through government web sites and private firms offering background checks to employers and realtors, which fuels criminal discrimination and gravely truncates the life-opportunities of ex-offenders years after they have served their sentence and “come clean” (Blumstein and Nakamura 2009). They would expand substance abuse treatment inside and outside prison since the vast majority of convicts suffer from serious alcohol and drug dependency and yet go untreated by the millions.

They would immediately divert low-level offenders who are mentally ill into medical facilities instead of continuing to subject them to penal abuse and medical neglect in carceral facilities as consistently recommended by leading public health experts for over two decades (Steadman and Naples 2005). They would stop the costly and self-defeating policy of returning parolees to custody for technical violations of the administrative conditions of their release (Grattet et al. 2008). The list goes on and on.

This post began with a discussion of Michael Vick’s situation and will end that way. If a rich athlete who is having his best season ever on the football field cannot engender good will from a vengeful and unforgiving public, what are the prospects for the 650,000 other people who are released from prison each year not named Michael Vick? If we are serious as a society about “second chances” and “reentry,” then we are going to need move beyond the “myth and ceremony” of those concepts to a radical shift of consciousness and a significant reallocation of resources. Otherwise, we should just stop the pretense and keep all prisoners behind bars for life which would seem to be fine with many Americans….

Update: I just came across this blog post by Dave Zirin. It looks like he is thinking along the same lines when he writes:

Michael Vick, whether he likes it or not, is humanizing the struggle to find redemption after serving time in a maximum security prison. After all, if a star quarterback doing hours of community service can’t regain a foothold in society, who could? Tucker Carlson’s efforts to dehumanize Vick and paint him as a disposable, killable individual, cuts in a way that transcends the idiocy of Murdoch’s 50 state southern strategy of dimples and dog whistles. I’d love for Carlson to spend even a week in Leavenworth and then make an effort to rebuild his nerfy little life. Then we’d see how a man without callouses could be so callous.