Guest Post: What We Have to Learn from the Casey Anthony Trial…A Feminist Assessment

This is a guest post from my good friend Chez Rumpf. Chez is a Ph.D. candidate in sociology whose work focuses on gender and the criminal legal system. Chez is a member of the Chicago PIC Teaching Collective. and a board member of the Chicago Freedom School.

I have been wanting to write about Casey Anthony. I have put off writing about this woman and the trial that captivated a large portion of the United States for a few reasons. First, I kept waiting for someone else to write about her. Let me clarify – I kept waiting for someone to write a feminist reaction to Anthony’s case and trial.

Throughout the sensationalized media coverage of the case, spearheaded by Nancy Grace and her “Tot Mom” moniker for Anthony, something just didn’t sit right with me. It was clear that Anthony was not only (or maybe even primarily) being judged for allegedly killing her daughter; rather, she was being judged for not fitting our conventional ideas of what motherhood looks like. She was too young, “hot,” unrepentant, tattooed, and interested in partying. Even without the murder and cover-up allegations, it was clear to the world that Casey Anthony was not a “good” mom. Yes, people pointed out legitimate concerns that seemed to implicate Anthony in her daughter’s death. But it was the picture of Anthony dancing in a nightclub in a too short dress that endlessly circulated on television and the Internet and acted as another damning piece of evidence against her.

When Anthony was found “not guilty” of the most severe charges the state brought against her (first-degree murder, aggravated child abuse, and aggravated manslaughter of a child), I eagerly awaited an outpouring of feminist analysis on what the verdict can tell us about society. With the exception of an insightful blog by Julie Moos at Poynter.org, I’m still waiting.

A second reason that I’ve put off writing about Anthony is that, frankly, I’m weary of the backlash that mentioning her name without condemning her in the next breath almost inevitably provokes. The Chicago PIC Teaching Collective, of which I’m a member, frequently grapples with the question: “What about the bad people?” Whenever we facilitate a PIC 101 workshop or talk about prison abolition, this question comes up. And by all means, if you believe the picture that the prosecution painted, Casey Anthony is one of the “bad people.” Part of why it is difficult to answer the “What about the bad people” question is because often it is intended to close off rather than open discussion. The question often is used to silence those of us who want to imagine a world without prisons.

My hesitation to write about Casey Anthony was a strong reminder of how powerful the PIC ideology is in our society. It often operates without notice. It shapes and limits our thinking. It closes off questioning. What is there to say about a young woman who allegedly murders her daughter, makes up stories for the police, and then dances on tables in nightclubs?

The PIC tells us that there is nothing to say. She is a monster. There are no questions to raise here. There is no understanding to seek. Convict and sentence her. Let’s keep the system chugging forward, no questions asked. As Nancy Grace told Jay Leno during a recent appearance on “The Tonight Show,” when she was a prosecutor she learned that “It doesn’t matter why. It matters who did this thing. That’s what I’ve got to prove.” This simplistic, narrow-minded thinking makes me cringe. The thought that such thinking is pervasive among prosecutors, judges, and other state agents overwhelms me.

In an effort to resist the PIC ideology, I’m forcing myself to write about Casey Anthony. I want to explore what Casey Anthony’s case can tell us about how embedded the PIC is in our society.

Tough on Crime = Tough on Mothers

One of the most telling aspects of the Casey Anthony case is the public reaction to the not-guilty verdict, issued on July 5th. That same day, a petition was created on Change.org to demand that the President, House of Representatives, and Senate enact “Caylee’s Law” – federal legislation that would make it a felony for parents, guardians, or caretakers not to report a missing child to law enforcement within 24 hours of the child going missing. As of August 2nd, 1,284,871 people had signed the petition.

As comments left by many of the petition’s signers make clear, the intent behind this proposed legislation is not to save children’s lives. People who are advocating for this law are angry that Casey Anthony is no longer incarcerated. The underlying thought process is if we couldn’t get Casey Anthony sentenced to death or incarcerated for life because she was found not guilty of the charges that would carry the severest sentences, then let’s create a law that would have allowed us to incarcerate her for a longer period. By extension, let’s create more laws that would provide more opportunities to lock up more people up for longer periods of time.

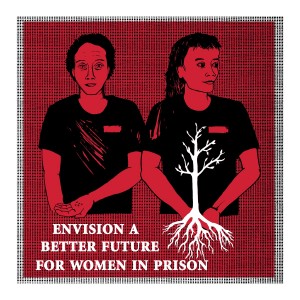

So, in the name of protecting children, Americans are rushing to enact tough on crime policies that would expand the ever-growing reach of the PIC. Importantly, these policies target women and mothers. While “parents,” “caretakers,” and “guardians” explicitly are gender-neutral terms, implicitly, they all refer to women. We know that women continue to do the vast majority of caretaking in this country. Given the persistence of traditional gender norms and the gendered division of caretaking, it is unavoidable that policies addressing caretakers are policies that address mothers.

“Caylee’s Law” is just the latest in a long line of legislation that criminalizes mothers in the name of protecting children.

The National Advocates for Pregnant Women documents how the War on Drugs targets pregnant women who have substance abuse problems. According to NAPW, “In the last twenty years, hundreds of pregnant women and new mothers have been arrested, based on the argument that a pregnant woman’s drug use is a form of abuse or neglect.” A 2003 article by Silja J.A. Talvi in The Nation tells the story of Regina McKnight, a young woman in South Carolina who was convicted of murder for a stillbirth. Although the state could not prove that McKnight’s use of cocaine while pregnant caused the stillbirth, the state prosecuted McKnight and won the case, resulting in a 12-year prison sentence. At the time the article was published, “Approximately 275 women nationwide [had] already faced charges relating to drug use during their pregnancies.”

As is characteristic of the U.S. criminal legal system, the state uses these child abuse and drug laws to target low-income women of color. In Shattered Bonds: The Color of Child Welfare, Dorothy Roberts explores how racial bias and discrimination systematically operate throughout the U.S. child welfare system. Roberts explains:

Part of the reason for the racial disparity in removal of drug-exposed newborns is that substance abuse by indigent Black women is more likely to be detected and reported than substance abuse by other women. The government’s main source of information about prenatal drug use is hospitals’ reporting of positive infant toxicologies to local child welfare authorities. This testing is performed almost exclusively by public hospitals that serve poor minority communities. Private physicians who treat more affluent women tend to refrain from testing their patients for drug use and certainly would be unlikely to turn them in to child protective services.

But racial discrimination – not just poverty – plays an independent role in decisions about drug-infected infants. Research confirms that, controlling for other variables, Black women are far more likely to be reported for prenatal substance abuse and to have their newborns placed in out-of-home care. A study of pregnant women in Pinellas County, Florida, published in the 1990 New England Journal of Medicine, found little difference in the prevalence of substance abuse along either racial or economic lines. Yet Black women were ten times more likely than whites to be reported to government authorities. A 1993 study of women whose newborns tested positive for cocaine in New York City hospitals discovered that Black women were 72 percent more likely than white women, and more than twice as likely as Latino women, to have their babies removed by child protective services. (P. 50-51)

We have seen how these so-called child protection laws not only fail to protect children from harm but perpetuate the racist reach of the state (i.e. the PIC and the child welfare system). Yet, much of the American public continues to push for more of this “feel-good” legislation – legislation that allows politicians to appear as if they care for the “deserving” vulnerable members of our society (that is, children) while winning election and re-election by supporting policies that prey on the “undeserving” vulnerable members of our society (that is, low-income people of color).

It’s time to speak out!

Feminists, anti-racists, and anti-violence activists cannot afford to remain silent on the Casey Anthony trial. Yes, it’s tempting to ignore the spectacle and write it off as nothing more than fodder for mainstream media sensationalism. The Casey Anthony trial, however, is very real and very important in its consequences. In a rather cruel irony, the white privilege that most certainly contributed to Casey Anthony’s not-guilty verdict now is poised to contribute to the expansion of the PIC and continued targeting of low-income women of color. We cannot risk quietly standing by while the state, once again, uses children to advance racist, punitive legislation that emboldens the PIC.