“The Slaves of Turpentine:” A First Hand Account of Convict Leasing

As part of my ongoing interest in the history of prisons in the U.S. and especially in the convict leasing system, I am sharing excerpts from an article published in a magazine called “The Literary Digest” in June 1914. I came across this article as part of my research. I think that too few people truly understand the evolution of the criminalization and incarceration of black people in the U.S. As you read this account of a convict camp in Florida in the early 20th century, think about the parallels to what we see in many prisons today. Below are excerpts from the article:

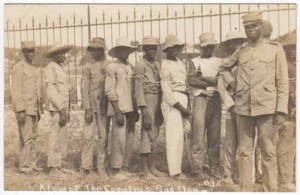

“In the turpentine convict camps of Florida are human beings whose “degraded, debased, sordid” existence is “worse than any exile, worse than any slum district,” worse, even, “than Whitechapel, London.” So writes Marc N. Goodnow in the Continent (Presbyterian, Chicago, June 4), after a ten-days’ visit to one of these camps employing negro convicts — prisoners of the State. “No penitentiary in this country has ever equaled the sordidness of this or the other thirty camps in that State; no condition of servitude or savagery that I ever heard or read about has ever surpassed the state of inhumanity or hopelessness behind the whitewashed stockade of this camp.” The needs of the ignorant mountaineers of the South, declares Mr. Goodnow, “are as nothing compared to the oppression of these slaves; yet the former are aided in missions” and the latter receive no religious help and are “apparently unknown” to generous Christian givers. In the camp this writer particularly describes there are thirty-five negro men, “in all stages of human dilapidation.”

“In the turpentine convict camps of Florida are human beings whose “degraded, debased, sordid” existence is “worse than any exile, worse than any slum district,” worse, even, “than Whitechapel, London.” So writes Marc N. Goodnow in the Continent (Presbyterian, Chicago, June 4), after a ten-days’ visit to one of these camps employing negro convicts — prisoners of the State. “No penitentiary in this country has ever equaled the sordidness of this or the other thirty camps in that State; no condition of servitude or savagery that I ever heard or read about has ever surpassed the state of inhumanity or hopelessness behind the whitewashed stockade of this camp.” The needs of the ignorant mountaineers of the South, declares Mr. Goodnow, “are as nothing compared to the oppression of these slaves; yet the former are aided in missions” and the latter receive no religious help and are “apparently unknown” to generous Christian givers. In the camp this writer particularly describes there are thirty-five negro men, “in all stages of human dilapidation.”

The State still reserves its “right to trade and barter” in their black bodies, “leasing them to an association for the sum of $281.60 a head per annum, and allowing that association to turn to lease them to individual camp contractors for the sum of $400 a head per annum.” The average profit on this transaction of $100 a head for 1,500 convicts is “easy money.” The convicts’ first sight of the “clump of low, white buildings, squatting under a blazing sun in a desert of sand and marsh, turns them sick.” And for many days they have to be closely guarded for fear of attempts to escape. In their embitterment and weariness, the one saving grace is their “irresponsible temperment,” which combines with a “mad desire to forget” to cause occasional evening and Sunday hours of merriment. But to let Mr. Goodnow describe a typical day in the camp:

“The day’s work begins out in the turpentine forest by the time the sun strikes the hooded tops of the slender, swaying pines, which means that the convicts are astir in the fetid bunk- and mess-rooms of the stockade building some time before. A hurried “bait” of salt meat and biscuit or corn pone breaks their fast; they file out of the stockade, hatless, coatless, bootless, and take their places in separate squads of ten to fifteen each, according to their duties in the woods. Then they begin the tramp — which may be several miles to work — an armed guard or two on horseback and a couple of hound dogs trailing along behind.

“The day’s work begins out in the turpentine forest by the time the sun strikes the hooded tops of the slender, swaying pines, which means that the convicts are astir in the fetid bunk- and mess-rooms of the stockade building some time before. A hurried “bait” of salt meat and biscuit or corn pone breaks their fast; they file out of the stockade, hatless, coatless, bootless, and take their places in separate squads of ten to fifteen each, according to their duties in the woods. Then they begin the tramp — which may be several miles to work — an armed guard or two on horseback and a couple of hound dogs trailing along behind.

“The squad dips fresh pine resin from boxes cut at the base of the trees or scrapes the hardened gum from the open face of the tree-trunks. The work carries the men through infested swamps and marshes up to their waists; it holds them through rain or shine, hot or cold. There is no protection for their bodies; the convict stripes are tattered flannel and are worn without underwear. The dew is not yet off the thick grass palmetto stubble when they go to work and it is cold and dank.

“But the day’s stint has already been set and the squad works rapidly and furiously, the men running back and forth, back and forth, between the trees and the barrels which hold the resinous gum and pitch.

“It is dark when these tired, silent, ghostlike wretches file back into the stockade — perhaps wet to the skin and muddy with feet and legs torn and bleeding from contact with the sharp blades of the palmetto. The stockade is a welcome sight after a day in the woods, for it means rest and sleep or perhaps an evening diversion. Even supper of cold baked beans, fat meat, and corn bread will stir life afresh within these creatures. The plank, plink, plank of the banjo is enough. It starts a shuffle of feet and the fancy evolutions of the buck and wing begin.”

Sometimes on a Sunday, if prosperous-looking visitors make it seem worth while, a half dozen of the more talented convicts will put on a “show” or a dance.

“And while this show is in progress, several guards and dogs, and at least one of the convicts are absent. The guards are following the baying hounds through the forest. The dogs are following the trail of a convict as he speeds through the stubble of the woods, dodging here and there to throw the hounds off the scent, or – when the pursuit grows too hot – “shinning” to the top branches of a tree.”

This is the “nigger chase,” a weekly rehearsal to keep the dogs in training for the capture of some wretch who makes a break for liberty. Once.

“Nine convicts escaped from the bunk-room one dark night while the guard slept. To lose $3,600 in one night is rather expensive, even for a camp where the profit from turpentine and resin the year before is said to have been $25,000. And then, on top of this, of the six dogs that gave chase through the woods in a futile effort to capture the fugitives, three died. This was even a greater loss than the convicts or the money, for a hound-dog with a good nose for scenting convicts is an object of no little pride and care in a turpentine camp.”

[…]

There is no hope from within the camps, we are told. Magazines, books, and newspapers which Mr. Goodnow brought for the prisoners were kept by the guards. “There is supposed to be a library of some sort at each camp, but there is nothing of the sort.” It is said that nothing can be done for these convicts. “Florida has allowed this slavery system to grow and thrive for thirty-two years without turning a hand to better conditions.” But, declares Mr. Goodnow finally —

“The fact that this inhuman system has been allowed to flourish not only in Florida but in Alabama and other States for so long is all the more reason why the church — some church at least — should attempt some systematic mission work. When society exiled these creatures to malarial swamps, fever-breeding bayous, insanitary, sleeping and eating quarters, inhuman practices, and the hardest kind of physical labor, it forgot that these men would one day reenter society. The question is: ‘What kind of men will they be?’

“There may be no complete regeneration ahead of these men, at least not while they are so utterly neglected by civilizing influences, but how immeasurably their mental, moral, and spiritual outlook could be improved by the kindly, human, sympathetic influence of the church? Where is the church that will accept this mission?“