Parole: Life on the Outside

In his book, 7 Long Times, Thomas writes movingly and searingly about his incarceration. In particular, I found his description of parole to be insightful and to be worth sharing on this blog. This excerpt comes from the Appendix of the book (pages 180-181).

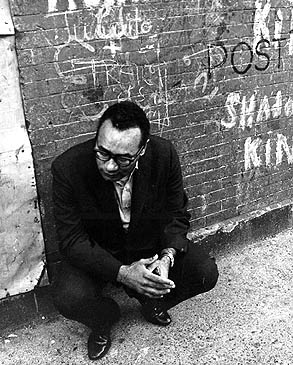

Before I was released from prison, the authorities filled my head with all kinds of threats and warnings of what would happen to me if I stepped out of line on the outside and how in the twinkling of an eye I could be back in the slams. I was to be an ex-con on parole with few or no civil rights. If I had been a second-class citizen before I went to prison, and a third-class citizen in prison, I was a fourth-class citizen upon my release.

In 1955, when I was released, there were no organizations working with parolees, with the exception of the Police Department, the Department of Corrections, and some religious groups. Parolees come out of prison badly shook-up, scared on the inside even if they didn’t show it. Very few can re-enter society with no sweat at all. It is a process that takes determination, time, and mucho patience. There is a high rate of recidivism because it is hard to make it on the outside. Face it, when jobs are hard to get on free side for non-offenders, being non-white and an ex-con makes it near impossible. Don’t care who you are. You’ve got to eat, dress, and have a place to sleep, and if you have a family, the burden is even greater. Many former inmates fight to go straight, but slowly find their way back to whatever got them in prison in the first place.

For me, parole was like a short rubber band that could snap me back into prison a million times faster than I had gotten out. My meager sense of being free on the outside vanished when my parole officer and probation officer, seeing me on Tuesdays and Thursdays, pounded into me that I was only out on parole, not free. Like if I fart in the wrong part of town, sir, I’ll find myself back in prison so fast it’ll make my head spin.

My parole officer would usually notify me when he was coming for a visit, but sometimes he would come around without notice. I wasn’t breaking any laws, unless making love is a crime, but according to the rules and regulations of parole, I wasn’t supposed to make love with anyone other than my legally wedded spouse. They got to be kidding!

One day I got real shook-up when my parole officer came to visit and I was standing on the stoop talking to Bayamon, who had just gotten out of prison. I froze and whispered to Bayamon, “Diggit, here comes my parole officer,” and Bayamon disappeared so smoothly and gracefully it was like he had vanished in a puff of smoke. If my parole officer recognized Bayamon as a parolee, he didn’t let on. I figured he probably knew that most of the parolees came from neighborhoods like mine.

Yet try as hard as I could to cool my role, I couldn’t help being nervous every time I reported and got visited. A parolee has no rights, and any bullshit complaint by a citizen can start him on his way back to prison. A parolee has got to walk on water because if he’s picked up on his way home while something is happening on the street — a fight, somebody else pulling a job, or whatever — he is in for sweat’s sake unless there is proof of innocence beyond a shadow of a doubt.

It was hard to deal with people who had never done time, especially when they knew I had. They would either clam up and look curiously at me or put on a big act of friendliness while also looking curiously at me. When I ran into an ex-con, it was like meeting a fraternity brother, even if I had hated his guts in prison.

It took me a long time before I was able to get the prison cockroaches out of my head. I’d wake up at home from nightmares that I was back in prison hearing the horrors, the curses and screams, reliving the tensions, anger, and pain, my body drenched in cold sweat. It would take minutes for me to realize I was at home.

When I first came home, I couldn’t break the habit of waking up in the morning half-asleep, getting into my clothes and stumbling around my bedroom looking for the toilet bowl and wash bowl, then standing like a damn fool in front of my bedroom door waiting for the guard to spring the lock. While in prison, I had always fought against being institutionalized, but some of its habits had rubbed off on me a little too damn deep. Even now, twenty-four years later, I still have an occasional nightmare that I’m back in prison.