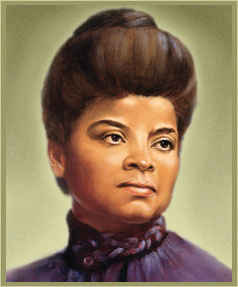

Ida B. Wells-Barnett & the Negro Fellowship League

I am reading another biography of Ida B. Wells-Barnett. This is the third one that I will have read and I continue to learn new things. If you live in Chicago and work on issues of criminal justice, then you should be required to become an expert on the life and work of Wells-Barnett.

I am reading another biography of Ida B. Wells-Barnett. This is the third one that I will have read and I continue to learn new things. If you live in Chicago and work on issues of criminal justice, then you should be required to become an expert on the life and work of Wells-Barnett.

I have long wondered why the Negro Fellowship League (NFL) hasn’t received more scholarly attention. The NFL was founded in 1908 by Ida B. Wells and a group of her Bible study class students. Wells built the organization into a reading room and social center which moved into a rented space in 1910. She received seed money for the move and to establish early programming from Mrs. Victor Lawson (wife of the owner of the Chicago Daily News). Wells biographer Mia Bay (2009) describes the activities of the NFL reading room in her book “To Tell the Truth Freely:”

“Staffed by one employee and a roster of volunteers, the NFL’s reading room was open from 9 a.m. to 10 p.m, and housed a ‘selected library of history, biography, fiction and race literature especially.’ It offered visitors a place to read, study, write letters, and pursue a’ quiet game of checkers, dominoes or other games that would not interfere with those who wished to read.’ Nonalcoholic refreshments were available…Visitors were also encouraged to attend weekly lectures by a variety of prominent speakers, ranging from white reformers such as Jane Addams and Mary White Ovington to black intellectuals such as William Monroe Trotter, Garland Penn, and the historian Carter G. Woodson. Free and open to the public, these events attracted local people as well as league members (p.285).”

The NFL was much more than just a reading room and social center though. It began to offer lodging to young men who had just migrated to Chicago; visitors could rent a bed for 50 cents a night. They offered food to those who needed it and helped people to find employment. In just its first year of operation, the employment bureau placed 115 men in jobs (Bay, p.286).

However, for me, the most interesting aspect of the NFL was its work to support prisoners and to protect black men in particular from injustice. This focus seemed most important to Ida B. Wells. She and her husband worked through the NFL to represent many young black men who were falsely accused of crimes and also to secure the release of convicted individuals.

While reading a local newspaper, Wells-Barnett’s attention was captured by the story of Chicken Joe Campbell. Campbell was already incarcerated at Joliet Prison when, in 1915, the warden’s wife was killed in a fire. He was accused of murdering her.

The warden, Edmund M. Allen had been appointed by the Governor of Illinois in 1913. He had very progressive views (especially for the time) about how to treat prisoners. “There is some good in every man…and there exists some influence which will appeal to his heart and reason (cited in Giddings, 2009, p.549).” Allen had instituted an “honor system” at the Prison that allowed inmates to be rewarded with privileges and better job assignments for good behavior. Joe Campbell had through his good behavior been elevated to the status of “trusty” and was assigned as a personal servant to the wife of the warden, Odette. Campbell was scheduled to appear before a parole board in a little more than a week when a fire broke out in the second-floor bedroom of the warden’s house. (Incidentally, Mrs. Allen had apparently agreed to testify in support of Campbell at his upcoming parole hearing). Paula Giddings explains what happened next in her authoritative biography “Ida: A Sword Among Lions (2008):”

“When prison guards and convicts from the volunteer fire department rushed to the residence, they found the lifeless body of Mrs. Allen. A later investigation found that alcohol had been spread over the bedding and that Mrs. Allen’s skull had been fractured. The coroner concluded that she had been knocked unconscious before succumbing to smoke inhalation and the flames. The Allen’s physician, who also had access to the warden’s living quarters and was himself a convict in the prison for killing his wife, claimed that Odette Allen had also been strangled and sexually assaulted — thought he had not made a thorough examination and no secretions were analyzed (p.549).”

Joseph Campbell was arrested for the crime right away. Ida B. Wells read about his plight when the Chicago papers reported that Campbell had been “confined to solitary in complete darkness for fifty hours on bread and water (Bay, p. 292).” After 40 hours of being subjected to questioning, Campbell ‘confessed’ to the crime. Wells was appalled by this barbaric treatment and wrote an outraged letter and appeal to local papers. “Is this justice? Is this humanity? Can we stand to see a dog treated in such a fashion without protest?” she wrote. She didn’t stop there. She sent her husband, Ferdinand, to represent Campbell because she felt that the “prominent people” in Chicago weren’t supporting him. Ferdinand was told by prison officials that Campbell already had an attorney (it turned out that this was not true). Persisting Ida wrote a letter to Campbell himself and went to see him at the prison. She came away convinced of his innocence. When she returned to Chicago, she found a letter that Campbell had sent in response to her original letter to him. It was subsequently published in local and national papers and proclaimed his innocence of the charges against him:

Ida and Ferdinand threw themselves into the defense of Joseph Campbell. Ida tirelessly raised funds while Ferdinand defended him in court. Despite Ferdinand’s best efforts, Joseph Campbell was found guilty and sentenced to death in April 1916. Ida and her husband supported Campbell through three appeals. After the final appeal, Campbell’s sentence was commuted by the Governor from death to life in prison in large part due to the pressure that the Barnetts kept up in this case. Campbell died in Joliet prison in 1950, nineteen years after Ida herself had passed.

On days when I am feeling run down and exhausted from working to dismantle this criminal injustice system, I think of Ida B. Wells. Wells was able to secure individual contributions and some grant funding for the first couple of years of the NFL’s existence but then had to sustain the organization from 1913 until 1916 with her $150 dollar monthly salary from her work as a probation officer. Due to a lack of funding, the NFL had to close its doors in 1920. Some of the reasons that she could not secure funds for her work were because many considered it to be radical and also because she refused to cow-tow for wealthy philanthropists. As someone who has to struggle every single day to sustain a grassroots organization, I can understand the frustrations that Wells must have felt. I am in no way comparing myself to Wells-Barnett (because that would be preposterous) but I do know what it is like to work for “free” and to also have to basically subsidize my activism with my own funds. I know many other friends who are doing the same.

What I respect most about Ida is her integrity and her uncompromising dedication to supporting the most marginalized people “by any means necessary.” I take pride in the fact that I get to live and work in a city where she made her mark and left such an important (yet still hidden) legacy. Here’s hoping that some enterprising scholar is hard at work uncovering more about the work of the NFL.

Note: For those interested in prison photography, Richard Lawson has curated some images created by Joliet prison inmates from 1890 to 1930. This period overlaps with part of the years that Joseph Campbell was incarcerated there and that Ida B. Wells-Barnett would have been visiting prisoners.