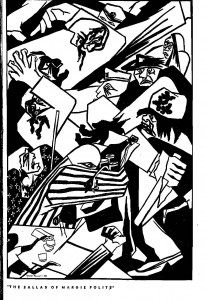

Margie Polite, Police Violence, and the 1943 Harlem Riots

This is another excerpt from my Resistance to Police Violence in Harlem pamphlet that was published in May. This time, I focus on the 1943 Harlem Riots.

** All references can be found in the pamphlet.

We don’t know for sure how or why Marjorie (Margie) Polite came to be at the Hotel Braddock on August 1, 1943. We only know for sure that she was there and that she was causing a fuss. The reasons for her ill temper are in dispute.If Margie Polite

Had of been white

She might not’ve cussed

Out the cop that night…

She started the riots!

Harlemites say

August 1st is

MARGIE’S DAY.– Langston Hughes

In some accounts, Margie Polite checked into the Hotel Braddock on West 126th street in Harlem. She complained about her assigned room and was moved to another one. She was still not satisfied with the amenities in her new room so she asked for a refund and checked out. Before she left the hotel though, she asked that the elevator operator return a dollar tip that she had given him. The man denied receiving a tip from her and Ms. Polite became incensed. She was belligerent.

In other versions of the story, Margie Polite was at the Hotel Braddock attending “a raucous drinking party in one of the hotel’s rooms.” She was drunk and loud.

A rookie patrolman named James Collins was stationed at the hotel and asked Ms. Polite to leave. She berated him and resisted. He put her under arrest for disorderly conduct. By this time, another woman, Mrs. Florine Roberts, approached the front desk where the commotion was taking place in order to pick up her checked bags. Mrs. Roberts had been staying at the hotel while visiting her 26 year old son, Robert Bandy, who was on leave from the Army. She and her son, Private Bandy, demanded that officer Collins release Ms. Polite who he had a tight hold on.

According to the official police report, Bandy and his mother Mrs. Roberts threatened patrolman Collins. They were accused of attacking him with Robert Bandy eventually grabbing hold of Collins’s nightstick and hitting the officer over the head. Patrolman Collins fell to the ground and Bandy tried to run. Collins said that he asked Bandy to halt and when he did not, the police officer (who was still on the ground) fired his revolver, wounding Bandy in the left shoulder.

Domenic J. Capeci Jr. (1977) offers an account of the incident from the perspective of Robert Bandy: “Bandy contended [sic] that he protested when Collins pushed Miss Polite, and the police officer reacted by throwing his nightstick, which Bandy caught; when the soldier hesitated to return the weapon, Collins shot him.”

Private Robert Bandy was transported to the hospital with only superficial wounds. Within minutes of the incident however, rumors swirled across the community that a black soldier had been shot and killed by a police officer while he was protecting his mother from harassment. In response, crowds of people gathered in three locations: the Hotel Braddock, Sydenham Hospital, and at the 28th precinct stationhouse. Some in the angry crowds began to throw stones and break windows; this set off a significant riot throughout Harlem. Capeci (1977) describes the scene once the riot ended on the morning of August 2nd:

It took 6,600 city, military, and civil police officers; 8,000 state guardsmen; and 1,500 civilian volunteers to finally end the riot after nearly two days. At the end of the 1943 Harlem Riot, according to the NYPD, six black people were dead (five were shot by police) and 185 were injured. However some media reports suggested that there were as many as 1,000 people hurt during the riot (including 40 police officers). More than 550 black people were arrested and a total of 1,485 stores were damaged and looted. Estimates of the damage ranged from $250,000 to $5 million dollars.“Harlem’s main thoroughfares, especially West 125th Street and parts of Seventh and Eighth Avenues, ‘looked as if they had been swept by a hurricane or an invading army.’ The scene was one of smashed windows, wrecked stores, and cluttered sidewalks, with broken glass, foodstuffs, clothing, and assorted debris everywhere.”

This riot didn’t emerge from out of the blue. Once the U.S. entered World War II after the 1941 Pearl Harbor attack, blacks across the country were hopeful that their economic prospects might improve. However, many, including those living in Harlem, found that the war effort failed to improve their economic and social fortunes. In fact, as was the case during World War I, black soldiers continued to face racism and discrimination within the armed forces as well as when they returned home after having fought for the U.S. abroad. Additionally, relations with law enforcement continued to be fraught with conflict and consistent harassment. In the aftermath of the 1943 riot, Adam Clayton Powell, Sr reflected on what provoked Private Bandy to stand up to Patrolman Collins: “When Bandy hit Collins over the head with that club, he was not mad with him only for arresting a colored woman, but he was mad with every White policeman throughout the United States who had constantly beaten, wounded, and often killed colored men and women without provocation.” Harlemite & renowned poet Langston Hughes also captured the realities facing Blacks of that period in his poem titled “Beaumont to Detroit: 1943.”

Looky here, America

What you done done –

Let things drift

Until the riots come.Now your policemen

Let your mobs run free.

I reckon you don’t care

Nothing about me.You tell me that hitler

Is a mighty bad man.

I guess he took lessons

from the ku klux klan.You tell me mussolini’s

Got an evil heart.

Well, it mus-a been in Beaumont

That he had his start –Cause everything that hitler

And mussolini do,

Negroes get the same

Treatment from you.You jim crowed me

Before hitler rose to power –

And you’re still jim crowing me

Right now, this very hour.Yet you say we’re fighting

For democracy.

Then why don’t democracy

Include me?I ask you this question

Cause I want to know

How long I got to fight

BOTH HITLER–AND JIM CROW.

After the 1943 riot, there wouldn’t be another major rebellion in Harlem until 1964. However, in the interim, police and community relationships remained conflict-ridden and untrusting. A 1957 incident would set the stage for community residents’ more assertive and violent confrontations with law enforcement during the civil rights era.