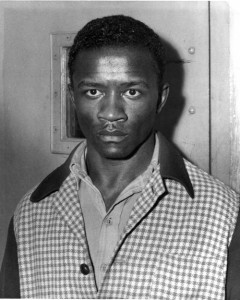

Willie McGee: the Politics of Race and Rape in the U.S.

I finally finished an excellent book titled “The Eyes of Willie McGee” by Alex Heard. The story of McGee is one that underscores the intersections between race and rape in the United States. I highly recommend Mr. Heard’s book. He paints a complex portrait of this case. He points out the inconsistencies in a balanced way and never takes sides. However, the reader is left with a ton of questions and with a lingering sense that it is possible that an innocent man was executed.

When McGee was tried for the rape of Wilette Hawkins in Mississippi in 1945, he was found guilty by an all-white male jury after less than 3 minutes of deliberation. McGee suggested that he had been having an affair with Ms. Hawkins and that their sexual encounters were consensual. Over the next five years, several trials would take place to overturn his death sentence.

One of the people who got involved in McGee’s defense was a 31 year old Jewish woman lawyer named Bella Abzug. Bella Abzug was born in the South Bronx in 1920. She attended Hunter College in New York City where she joined the American Student Union (the student arm of the Popular Front). She became student body president at Hunter and actively organized against American involvement in World War II, as well as adding African American and Jewish history to the University curriculum. Later she attended Columbia Law School. Abzug was hired in 1948 by the Civil Rights Congress (CRC)—a New York–based communist legal defense organization – to represent Willie McGee. She traveled to Laurel Mississippi at great risk to herself to find local lawyers who would take on his appeals. Abzug and other McGee supporters were ultimately unsuccessful and on May 8, 1951 he was executed.

The story that Mr. Heard has written about this case reads a bit like a mystery. Below is an excerpt from the first chapter, you should read the whole book if you can:

THE STORY BEGAN in November 1945, when McGee, a longtime Laurel resident who worked as the driver of a wholesale-grocery delivery truck, was charged with breaking into a home in a middle-class white neighborhood and raping Mrs. Troy Hawkins, a thirty-two-year-old housewife and mother of three.

The rape allegedly happened in the predawn hours of November 2, a warm autumn Friday. As the still-traumatized Mrs. Hawkins told police after daybreak that morning, she was asleep in a front bedroom with a sick, twenty-month-old girl at her side. Her thirty-seven-year-old husband was in a room near the back of the house, having gone there after spending several hours helping Willette take care of the infant. She said she woke up and heard a man crawling toward her on the floor. In an instant, he was on top of her, smelling like whiskey and threatening to kill her and the child if she didn’t shut up and submit. Once he was done, he told her never to say a word about what happened or he would come back and kill her. Then he ran out the front door. Mrs. Hawkins said it was too dark to see the rapist’s face, but she knew he was black by the texture of his hair.

McGee became a suspect in part because he didn’t show up for work on Friday, but also because Laurel police found witnesses—including two male friends of his—whose statements seemed to place him in the vicinity at the time of the assault. He was arrested the next day in a nearby city, Hattiesburg, briefly taken back to Laurel, and then driven to jail ninety miles away in Jackson, the state capital. Jackson was home to a massive county courthouse with a two-floor, upper-story lockup that was considered safe from attacks by lynch mobs. Often in cases like this, black defendants were whisked away from wherever they’d been arrested and taken straight to the Hinds County jail.

The trial was held in early December, amid so much local hostility that the governor of Mississippi sent McGee back to Laurel under heavily armed guard. It lasted only a day, with an all-white jury sentencing him to death after deliberating for less than three minutes. There would be two more circuit-court trials—the first two verdicts were reversed on procedural grounds by the Mississippi Supreme Court—followed by a three-year period of state and federal appeals, including multiple appeals to the U.S. Supreme Court.