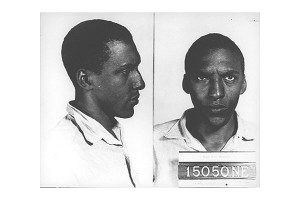

Bayard Rustin, the First ‘Freedom Rides,’ and Prison

I was perusing a used book store in Evanston last month and came across a first edition copy of Bayard Rustin’s collected writings. I am re-reading them now. I often wish that his contributions were better known. Those who do know something about him probably know that he was an ally to Dr. King and perhaps also that he was an openly gay man (at a time when that was perhaps as dangerous). Since we have spent the better part of this week discussing civil rights and the LGBT community, I thought that it would be fitting to revisit Rustin’s contributions since he isn’t a household name among the icons of the black freedom movement in the U.S. For me however, Bayard Rustin is/was a giant. In reading about the black freedom movement, I gravitated to him, Septima Clark, Fannie Lou Hamer and later Ella Baker as organizers of understated but unparalleled skill.

Rustin was a Quaker and a pacifist. In 1944, he was drafted & as a conscientious objector (CO) he refused to serve. For this, he was sentenced to prison:

Rustin was a Quaker and a pacifist. In 1944, he was drafted & as a conscientious objector (CO) he refused to serve. For this, he was sentenced to prison:

“On February 17, 1944, a court found Rustin guilty of resisting the draft and sentenced him to three years (most COs received one year and a day) in the federal prison in Ashland, Kentucky, a segregated prison in a segregated state. On one visit to white COs, Rustin was beaten by a white prisoner who only stopped when he realized that neither Rustin nor the other COs were fighting back. Rustin’s protests against racial segregation, and his open homosexuality, were a source of growing tension. So in August 1945, he was transferred to the higher-security penitentiary in Lewisburg, Pennsylvania, where he served out the remainder of his time.

In Lewisburg, Rustin was kept away from the nonpacifist inmates to avoid infecting them with “liberal” ideas. “By some prison officials we were considered the worst scum of the earth,” Rustin wrote after his release in June 1946, “because we had refused to fight for our country, and because we were college-educated. We used to say that the difference between us and other prisoners was the difference between fasting and starving. We were there by virtue of a commitment we had made to a moral position; and that gave us a psychological attitude the average prisoner did not have….. We had the feeling of being morally important; and that made us respond to prison conditions without fear, with considerable sensitivity to human rights… It was by going to jail that we called the people’s attention to the horrors of war.”

In the summer of 1944, Irene Morgan was traveling on a Greyhound bus to Baltimore. She was returning from a visit to her mother’s in Virginia. The bus became crowded. The driver asked Ms. Morgan to move and give up her seat to a white person. She refused. A deputy sheriff tried to arrest her and she resisted. “He put his hand on me to arrest me,” Ms. Morgan later recalled, “so I took my foot and kicked him. He was blue and purple and turned all colors. I started to bite him, but he looked dirty, so I couldn’t bite him. So all I could do was claw and tear his clothes.”

Ms. Morgan ultimately pleaded guilty to resisting arrest but refused to pay a fine for her crime. She was later represented by the NAACP when she decided to appeal her sentence. Her case, Morgan v. Commonwealth of Virginia, ended up in the U.S. Supreme Court where Thurgood Marshall and Spottswood Robinson argued that “segregated seating prohibited free movement from state to state.” The Supreme Court ruled in Irene Morgan’s favor. It declared that “state statutes requiring the segregation of races cannot be applied to interstate passengers.”

After this landmark ruling, a group of activists and organizers from the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE) and the Fellowship of Reconciliation (both which counted Rustin among their membership) resolved to test the Supreme Court decision. They organized a “journey of reconciliation” in 1947. It would be the first “freedom ride.”

Bayard Rustin explained (AUDIO) what the “Journey of Reconciliation” organizers had in mind:

In 1946 the Supreme Court of the United States delivered what became known as the Irene Morgan Decision. Irene Morgan was a black woman who had an interstate ticket on a bus. The Supreme Court ruled that she had been incorrectly arrested and punished, because if a person was moving between the states on a bus or train it was a burden on interstate commerce to stop the bus or train and waste time and energy separating people. You will also remember that 1946 is a crucial period, because many blacks who had been in the army were returning home from Europe. There were many incidents in which these black soldiers — having been abroad and exposed to fighting for freedom — were not going to come back to the United States on their way home and be segregated in transportation.

Therefore the combination of these blacks who were already resisting, and the Irene Morgan Decision, which gave blacks the right to resist segregation, particularly in interstate travel, we in CORE decided immediately following the Morgan decision that the next year, 1947, we were going to create a nationwide protest with nine blacks and nine whites who would go into buses all over the upper south with blacks sitting in the front and the whites sitting in the back to challenge this. This was known generally as the first Freedom Ride. It was called “the Journey of Reconciliation.” As a result of the Journey of Reconciliation a number of black and whites were jailed. That was my first experience on a chain gang. In late 1947, early 1948 I spent thirty days on a chain gang, as well as did a number of whites and other blacks.

Rustin wrote about his harrowing time on the chain gang in “Twenty-Two Days On A Chain Gang” (which was serialized & published in the New York Post. Thanks to the internet anyone who is interested can read about the brutal treatment that he & his fellow freedom riders endured in prison here (PDF). Rustin’s report contributed to abolishing the chain gang in North Carolina. The following short clip from the excellent documentary Brother Outsider speaks to both his role in the “Journey of Reconciliation” and his time on the chain gang in North Carolina.

Dr. King actually learned a lot about enduring his prison stays from Rustin. I’ve written in the past about intersections between the carceral state and the history of black protest. Rustin’s incarceration experiences are an illustration of these connections.

Some people know about the 1961 Freedom Rides which I have briefly written about here. Many more are unaware of the earlier 1947 Freedom Ride. Jerry Elmer writes in greater detail about this incident. You should read his account.