An Afternoon at Stateville Prison…

So I woke up on Thursday, got on the EL, met Amy and Tess, and together we drove out to Stateville. Along the way, I peppered Amy with questions: How many students were there? Would I have access to a computer to play some audio interviews? Could I bring the publications that I had with me inside the prison? She patiently responded to each query.

We arrive and go through the protocols. I leave my cell phone and purse in the trunk of Tess’s car. I store my valuables in a locker inside the visitor’s center. We hand over our identification, sign in and wait to be wanded and searched. We walk through three sets of gates and are checked against various lists. Then we cross through the yard on our way to our makeshift classrooms.

Along the way, we are greeted by various prisoners.”Good morning, how are you?” they call out. Three women (who aren’t guards) briskly walking through a maximum security prison is a happening. Finally, we arrive in the classroom. Tess sets up the audio while Amy and I move the chairs to form a circle. As we work, we’re greeted by a couple of prisoners who engage us in conversation.

Nehru, a student in Amy’s class, tells me that he was moved by my blog posts which are the required reading for the week. He’s written a response paper and asks if he can share it at some point during class. I’m thrilled that he connected with something that I wrote. “Of course, you can,” I enthuse. And just like that, I forget that I am inside a prison. I am just sitting in an uncomfortable chair talking about the fact that the U.S. is no country for black boys with another person. My nose is running and I realize that I have no Kleenex. Nehru springs up and comes back with toilet paper. “I’m sorry,” he says, “this is all we have.” In that moment, it’s everything. I thank him.

Soon the other men start to file in. Most are black and many middle-aged. The oldest man is in his 70s. Some greet me by name and everyone shakes my hand. I came to discuss why I care about prisons and my work with young people in conflict with the law. According to Amy, the session is highly anticipated.

I open by inviting the men to pick Angel Cards which I’ve spread out in the middle of the floor. I tell them to close their eyes and to think of the energy that they want to draw to themselves. They should then pick a card without looking at it. During introductions, I ask the men to share whatever they want about themselves and then to explain how the word on their Angel Card connects to their intentions for the week or to how they are feeling this day.

When it’s my turn, I introduce myself and tell a story. The men give me their undivided attention. It’s quiet and I can hear my scratchy voice recounting the pain of losing one student to death and another potentially to social death. As I speak, I share only pieces of my journey and of myself. After all, even though we often tell linear stories, our lives are seldom neatly ordered and besides time is short.

Later, I play audio of a young person who shared his story as part of my organization’s Chain Reaction project. The men listen intently. When I ask them to respond to what they heard, hands fly up. They speak of pasts marked by police harassment, lack of resources, and missed connections. Many men can see their own story in the one narrated by the young person through Chain Reaction. Their own interactions with the police are chilling, infuriating and unfortunately unsurprising. Gerald Reed is in the class and he is one of the survivors of Jon Burge’s torture. He understands first hand the abuse of police power.

I’m rapt as some of the men speak of transformation and of wanting to share what they’ve learned in their years behind the wall with those on the outside (most especially the young). The narrative of conversion is ever-present. The desire to prevent others from their fate is palpable.

We discuss semiotics and power. Are words like Nigger and Chiraq valuable and empowering or useless and destructive? We talk about disposability and of being made more killable. And time flies. Nehru reads his response paper and references Garvey, Delaney, Malcolm, and King. When he finishes, we all clap because it is wonderful. And I am reminded of why I still teach and of why I am not cynical about the importance of education.

We reach the end of the session and I share my address for those who want to write to me. The men thank me for coming. They invite me to return. I make no promises but I’d of course love to come again. As they leave, some of the men give me essays that they’ve written. Xavier hands me a letter that he must have written during class. One line reads: “I gave up my family to live in Stateville as a number, who am I?” The letter is filled with regret, pain, and hope that his son (who is facing his own drug case) will forgive him one day. It’s a cautionary tale titled “We-R-2 Young 2 Die Young.” It’s signed with his name and (The 4gotten one).

Only a very small number of prisoners can take courses at Stateville. My friends at the Prison and Neighborhood Arts Project have managed through hook and crook to organize and offer classes over the past couple of years. Their budget is minuscule and their commitment is the currency. We know that basic education programs in prisons help to break up the crushing monotony and in many cases can reduce recidivism. Yet across the country, throughout the 80s and 90s, prison education programs were dismantled.

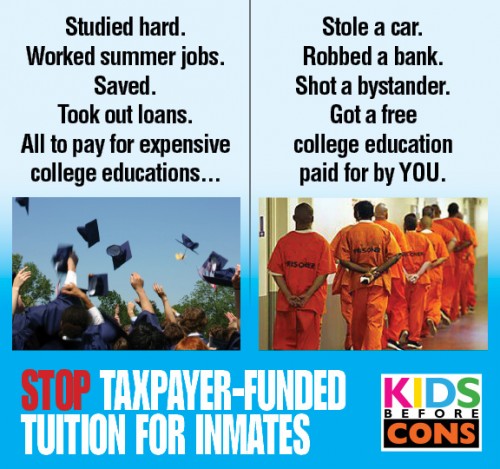

Recently, Governor Andrew Cuomo was demagogued into dropping his plan to “provide public financing for basic college-education programs in state prisons.” The racist imagery below was used in a petition campaign to get Governor Cuomo to drop his plan. The campaign was ‘successful’ but also cruel and short-sighted.

The men who I met at Stateville were among the best students I’ve had. They had done their homework. They were attentive. They engaged the material. They used critical thinking to analyze and connect ideas. They were hungry for more knowledge. While we were packing up to leave, one young man told me that he had read Michelle Alexander’s book “The New Jim Crow.” “It’s changed everything for me,” he confided, “I understand and see everything so clearly now.” And this perhaps is why the authorities have been and are so afraid of offering opportunities for formal education to prisoners and why so many people behind bars have relied on covert education. To read and to learn is to see one’s oppression more clearly. This is dangerous to the powerful.

As I left Stateville last Thursday, I thought about how often we delude ourselves into believing that we can put others away from us. We try mightily but it’s impossible: the disappeared have a funny way of not staying gone. Hard as we might try, we cannot wish others out of existence. We walk outside. I look back one last time and say I silent prayer, ‘Free them all.’