I co-curated two exhibitions in 2015. The second titled ‘Making Niggers: Demonizing and Distorting Blackness through Racist Postcards and Imagery‘ opened in October and will end its run at the end of this month. I worked with my friends Rachel Caidor and Essence McDowell to create the exhibition.

From the 1890’s through the 1950’s, thousands of postcards depicting racist caricatures and stereotypes of Black people were produced across the United States and the world. Degrading images of blackness also found expression in advertising and other media. In this propaganda, Black people were portrayed as lazy, child-like, unintelligent, ugly, chicken stealing, watermelon eating, promiscuous, crap-shooting, savage and criminal. These images represent some of the historical attitudes and beliefs about Black people. The stereotypes continue to shape and shorten Black lives in the present.

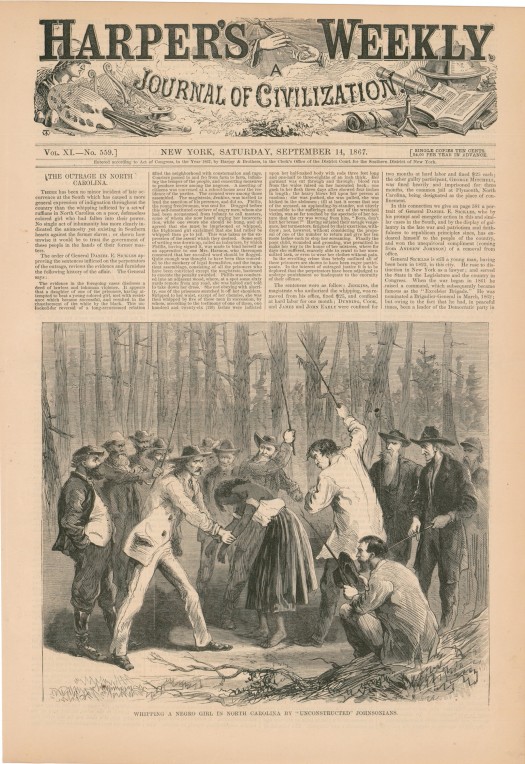

The widespread dissemination of negative stereotypes of Black people through popular culture had a distinct function. In an era (1890s-1920s) when the social order was violently disrupted, these images were deployed to comfort white people in their racist beliefs while also reinforcing white supremacy. The status quo needed to be preserved and violence against Blacks needed to be legitimated (or legitimized).

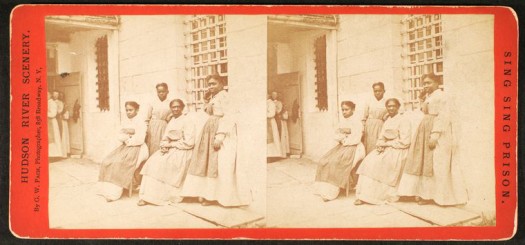

After Emancipation, many newly freed Black people were hopeful that with hard work and determination, they could overcome racial discrimination and injustice. As such, formerly enslaved people actively sought educational, economic and political opportunities. Throughout Reconstruction, “more than a quarter million Blacks attended more than four thousand schools established by the Freedmen’s Bureau (p. 23, Giddings).” Thousands of new Black businesses were founded. Tens of thousands of Black men registered to vote. Hundreds of Black newspapers were being published. The backlash against this Black success was swift and brutal.

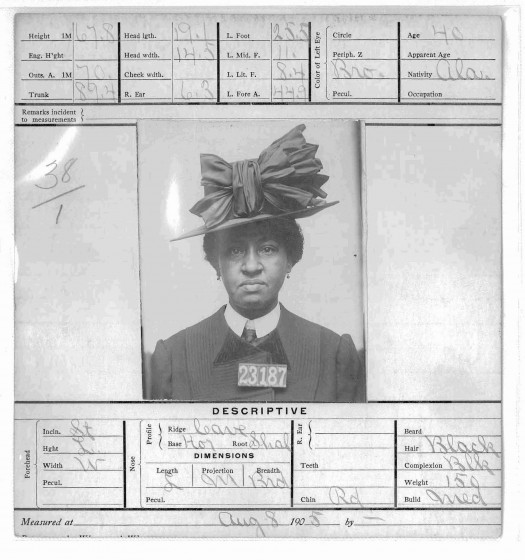

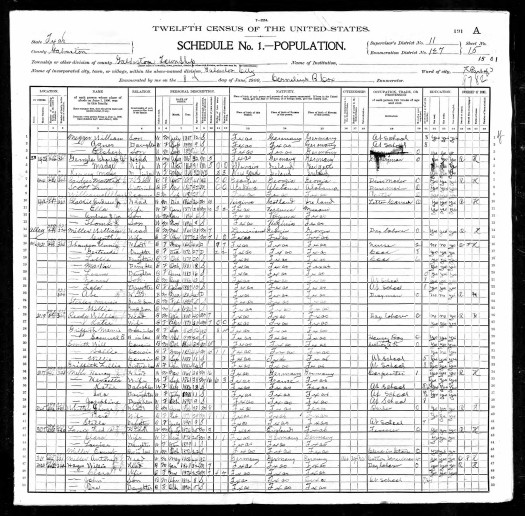

In the 1890s, lynchings “claimed an average of 139 lives each year, 75% of them Black (Without Sanctuary, p. 12).” The decades spanning the early 1880s through the early 1930s have been called the ‘lynching era’ by some historians. Journalist and activist Ida B Wells theorized that: “Lynching was a direct result of the gains Blacks were making throughout the South (Giddings, p. 26). Wells wrote: “[L]ynching was merely an excuse to get rid of the Negroes who were acquiring wealth and property and thus keep the race terrorized and ‘keep the nigger down’ (Giddings, p. 28).” Backed by a criminal punishment system that maintained and enforced white power & supremacy, Black people were subjugated, oppressed and exploited.

In this context, circulating negative images of Black people made them more vulnerable to violence. It also validated white people’s theories of Black inferiority, criminality, promiscuity and overall immorality. The ideas of Black inferiority and white supremacy are firmly entrenched. They formed the ideological basis of chattel slavery and continue in its afterlife.

Our exhibition illuminates the racist attitudes and ideologies that were/are endemic to U.S. culture and society. Relying primarily on postcards from my collection, this exhibition speaks to the legacy of anti-Black racism that still structures our present. The racist images underscore the ‘routine’ denigration of Black people. They illustrate how little Black lives have mattered in this country. They belie the need for a hashtag and a movement affirming that #BlackLivesMatter.

Postcards were accessible and low-cost means to disseminate anti-Black racist images and messages. It’s not coincidental that these types of postcards were most circulated from 1900 through the 1930s at the height of Jim Crow and spectacle lynching. The postcards offer further evidence that whiteness and white identity depended on Black subjugation and oppression. They illuminate the active “work’ of white supremacy to keep whiteness dominant. That work is a visible public project that allowed white people to define their own identities through the denigration and demonization of blackness. Black people did not escape this project unscathed. In a 1961 interview with Studs Terkel, the great writer James Baldwin explained that he moved to Paris in part to escape the stereotypes inflicted on Black people. He discussed the impact(s) of those racist images on Blacks:

“All you are ever told in this country about being black is that it is a terrible, terrible thing to be. Now, in order to survive this, you have to really dig down into yourself and re-create yourself, really, according to no image which yet exists in America. You have to impose, in fact – this may sound very strange – you have to decide who you are, and force the world to deal with you, not with its idea of you (Interview by Studs Terkel, Almanac, WFMT, Chicago 12/29/61).”

By viewing these racist images in the 21st century, do we perpetuate Black oppression or resist it? Are we complicit in the demonization and degradation of Black people by showing these racist & stereotypical images? We asked ourselves and others these questions before deciding to curate this exhibition. We decided to move forward because we believe that this history is important to underscore and to understand always & especially in our current historical moment. How did white people justify their continued subordination of Black people post emancipation? They did so in part, we contend, by actively making Niggers through creating and distributing racist stereotypes of Black people. We use the word Niggers knowing full well that it is controversial. Yet it is central to what we hope to convey through this exhibition. As Hinton Als writes, “Nigger is a slow death.” We are tracing a history of slow Black death-making on behalf of white supremacy. Ultimately, visitors to the exhibition will have to decide for themselves the answers to the above questions.

Our exhibition introduces a new generation to postcards as historical documents and cultural artifacts for understanding anti-Black racism in the past and present. Dozens of postcards tell stories of how Black people were devalued over time. Together these artifacts illuminate the ideological foundations of anti-Black racism in the U.S.

Hundreds of people have visited the exhibition so far. One of those visitors was the supremely gifted artist Damon Locks. Damon was inspired to create “Sounds Like Now,” a sonic response to the exhibition. He shared these words about the audio collage:

“I have been listening and thinking and rethinking. Yesteryear and today have been blurring into each other. I have record after record where people express eloquently their fight for freedom, justice and equality. Regardless of when it was recorded, it sounds like now. Take the needle off the record, back up and start again”

Listen to Damon’s performance of the audio collage.

You can also watch the performance.

Sounds Like NOW from ryan griffis on Vimeo.

I was personally blown away by Damon’s creative intervention. As I have been taking people on tours through the exhibition, I am struck by how few of them are familiar with the postcards even while being well-versed in the stereotypes that they convey. I’d hoped that the exhibition would add to the discussions currently happening around #BlackLivesMatter and it is. For those who are interested, we have a private Facebook group that we plan to use to continue the discussions we’ve begun even after the exhibition ends its run this month. Finally, we are working on a book that will feature some of the postcards and our commentary based on the exhibition. Stay tuned for that. We hope to release it this fall.