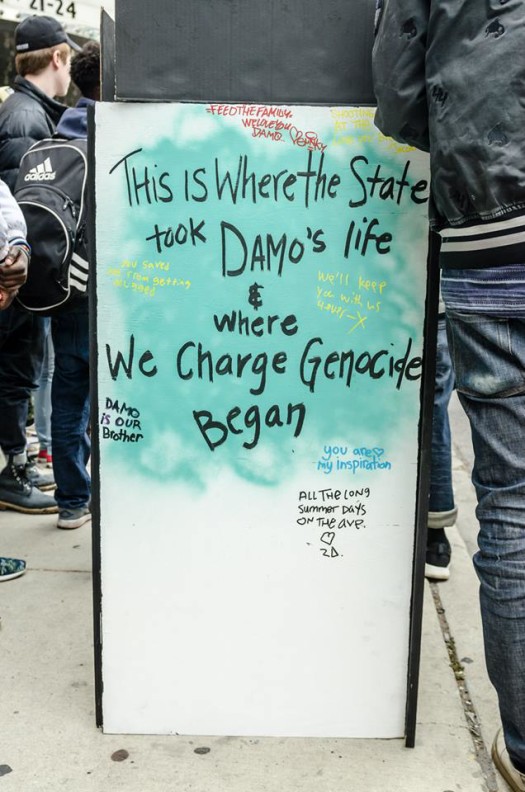

The 1970 edition of the “We Charge Genocide” petition included a preface by Ossie Davis. I recently re-read it and there was much that resonated with me. I’ve decided to re-publish his words not because I agree with every point that he makes or with all of the analysis but because I think that the essay echoes in our current historical moment. I’ve re-typed it faithfully.

Preface by Ossie Davis

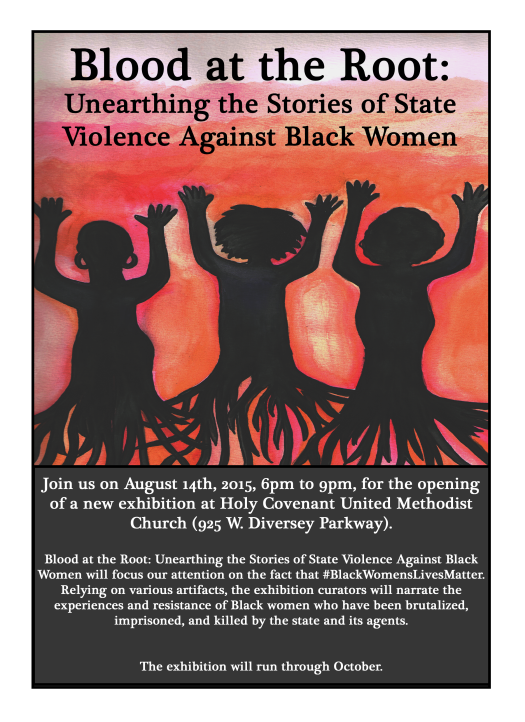

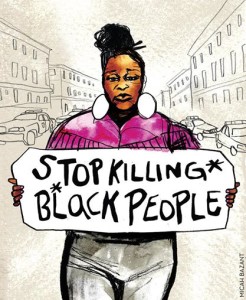

by Micah Bazant (2015)

This is not the first time the black people of the United States have issued a warning. W.E.B. Du Bois himself said it plain in 1900: “The problem of the Twentieth Century is the problem of the color line.”

We say again, now: We will submit no further to the brutal indignities being practiced against us; we will not be intimidated, and most certainly not eliminated. We claim the ancient right of all peoples, not only to survive unhindered, but also to participate as equals in man’s inheritance here on earth. We fight to preserve ourselves, to see that the treasured ways of our life-in-common are not destroyed by brutal men or heedless institutions.

We Charge Genocide! indeed we do, for we would save ourselves and our children. History has taught us prudence — we do not need to wait until the Dachaus and Belsens and the Buchenwalds are built to know that we are dying. We live with death and it is ours; death not so obvious as Hitler’s ovens — not yet. But who can tell?

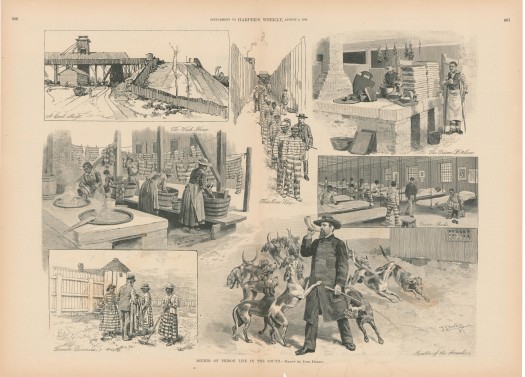

Black men were brought to this country to serve an economy which needed our labor. And even when slavery was over, there was still a need for us in the American economy as cheap labor. We picked the cotton, dug the ditches, shined the shoes, swept the floors, hustled the baggage, washed the clothes, cleaned the toilets — we did the dirty work for all America — that was our place, the place where the American economy needed us to be.

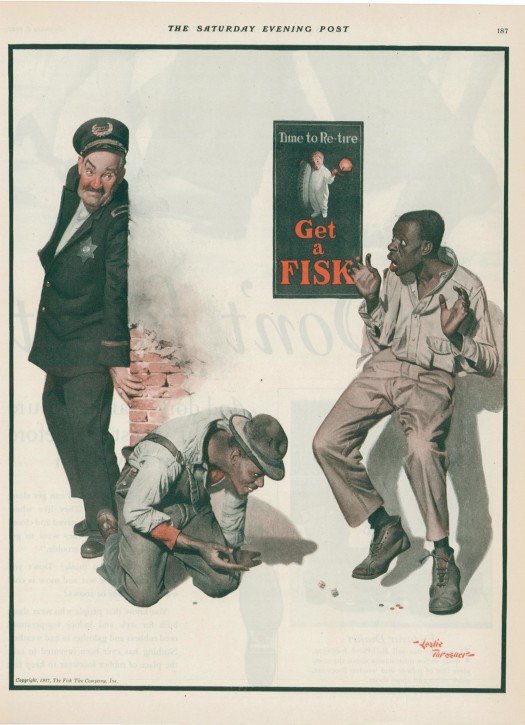

As long as we stayed in that place — there at the bottom — we were welcomed to love and work in America. The murder practiced against us then was partial and selective. A limited genocide meant not so much to exterminate us — America still had a job for “good niggers” to do — as to warn us, to correct us, to use those of us who would not submit as examples of what could happen to the rest of us. Those who objected to being kept in their “place” at the bottom were beaten or killed for being uppity. Those who challenged our racist overlords, claiming for themselves and for us our rights as men and as citizens, were burned for being insolent; lynched to teach the rest of us always to stay in our “place.”

But a revolution of profoundest import is taking place in America. Every year our economy produces more and more goods and services with fewer and fewer men. Hard, unskilled work — the kind nobody else wanted, that made us so welcome in America, the kind of work that we “niggers” have always done — is fast disappearing. Even in the South — in Mississippi for example — 95 per cent and more of the cotton is picked by machine. And in the North as I write this, more than 30 per cent of black teenage youth is unemployed.

The point I am getting to is that for the first time, black labor is expendable, the American economy does not need it any more. What will a racist society do to a subject population for which it no longer has any use? Will America, in a sudden gush of reason, good conscience, and common sense reorder her priorities? — revamp her institutions, clean them of racism so that blacks and Puerto Ricans and American Indians and Mexican Americans can be and will be fully and meanfully included on an equal basis?

Or, will America, grown meaner and more desperate as she confronts the just demands of her clamorous outcasts, choose genocide? America, of course, is not an abstraction; America is people, America is you and me. America will choose in the final analysis as we choose: to build a world of racial and social justice for each and for all; or to try the fascist alternative — a deliberate policy on a mass scale, of practices she already knows too well, of murderous skills she sharpens each day in Vietnam, of genocide, and final, mutual death.

We Charge Genocide — not only of the past but of the future. And we swear: it must not, it shall not, it will not happen to our people.

August 17, 1970.